Recent research has shed new light on killer whales’ genetic and behavioural diversity along the Pacific coast of North America. In particular, “Resident” and “Bigg’s” killer whales (after Canadian scientist Michael Bigg, sometimes referred to as “Transients”), previously considered distinct ecotypes within a species, may soon be recognised as distinct subspecies or even separate species.

These findings come from the research of Phillip Morin and colleagues, who addressed genetic differences and millennia-old evolutionary trends and distinguished the two groups in their behaviour, diet, and social structures.

Differences in behaviour, genetics, and ecology

As early as the 1970s, Michael Bigg observed that although Resident and Transient Orcas often inhabited the same coastal waters, they did not mate or interact with each other. These findings led to the classification of Southern Resident Orcas as a distinct population segment, which granted them protection under the Endangered Species Act in 2005.

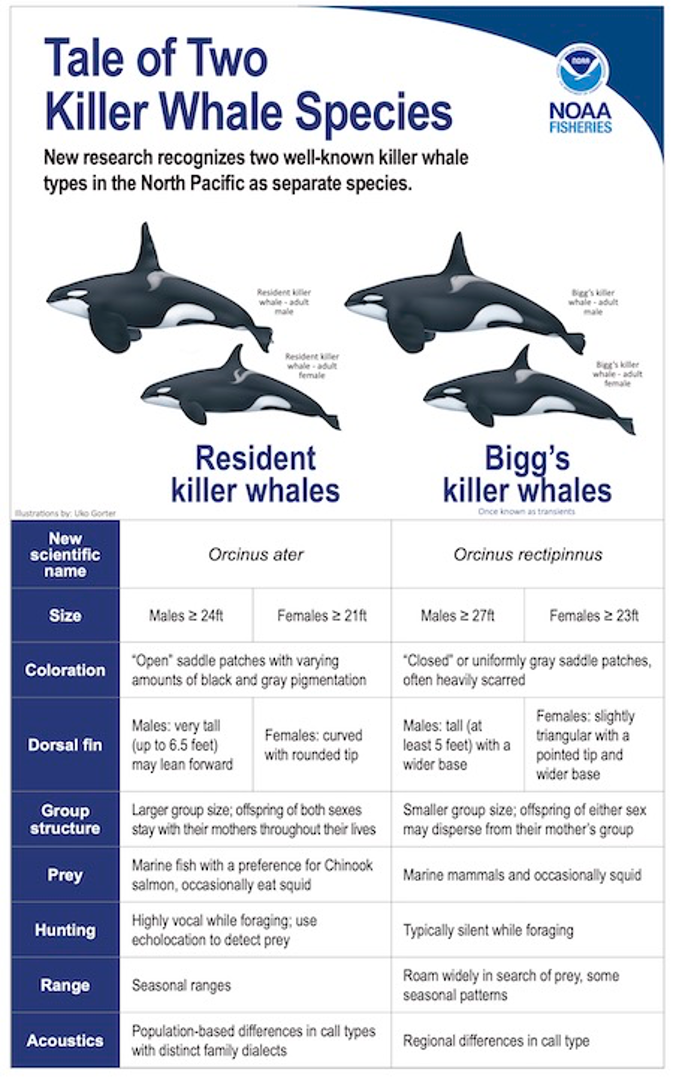

Recent genetic, physical, and behavioural research sponsored by NOAA and other institutions now confirms that the two ecotypes may, in fact, be distinct species.

The Resident Orcas are characterised by their preference for fish, especially salmon, and their distinct social structure. These animals live in close and stable family groups, known as pods, and frequently interact with each other.

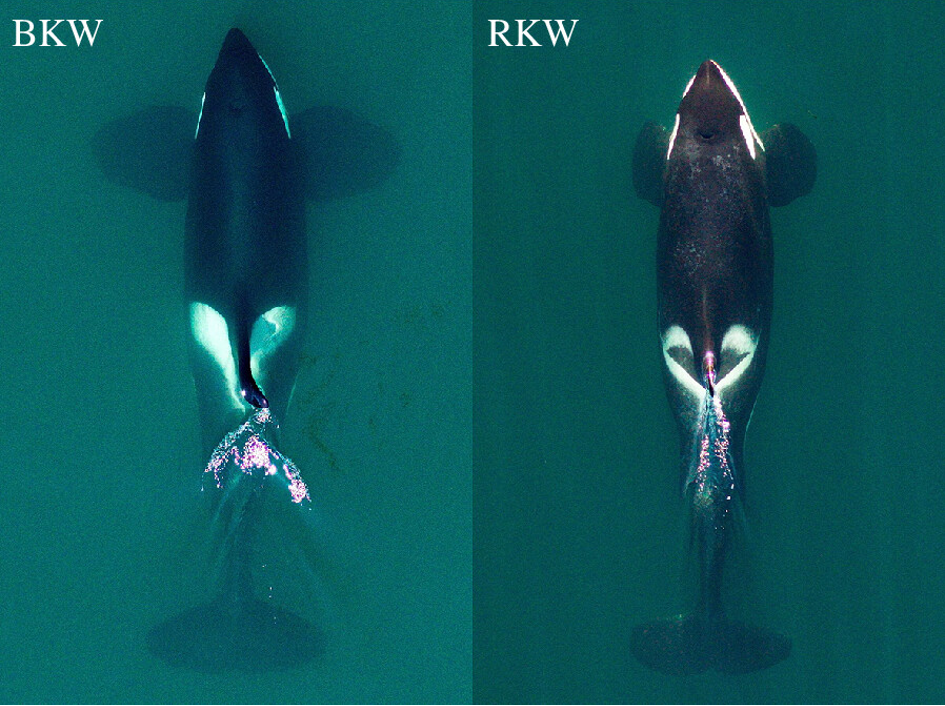

Source: Morin et al. (2024), showing a top view on Bigg’s Orcas (left) and Resident Orcas (right)

Their communicative behaviour, consisting of squeaks, calls, and whistles, is also very pronounced. In contrast, “Bigg’s” Orcas specialise in hunting marine mammals, including seals and smaller whales. This group hunts in smaller, more flexible groups to catch their prey more efficiently and primarily uses non-verbal communication to avoid drawing their prey’s attention to them.

These differences in hunting behavior and social structure are not just superficial adaptations but are deeply rooted in the DNA of the two groups. Genetic analyses have shown that these ecotypes have developed separately for over 300,000 years, indicating significant evolutionary differences.

Nevertheless, for a long time, they were only considered different ecotypes or unnamed subspecies of the Orcinus Orca. In their work, Phillip Morin and his team now concluded that the two groups should be listed as separate species in the future.

In accordance with their claim, the taxonomy committee of the Society for Marine Mammalogy included these latest findings in its annual report at the beginning of September 2024 and declared that although they do not yet consider the Resident and Transient Orca groups of the Pacific coast to be independent species, they nevertheless nominate them for the status of a subspecies of Orcinus Orca:

“The Taxonomy Committee completed its annual review of the official Society for Marine Mammalogy list of marine mammal species and subspecies for 2024. […] The updated list also includes the addition of three killer whale subspecies: Orcinus orca ater (resident killer whale) and O. orca rectipinnus (Bigg’s killer whale), with O. orca orca (common killer whale) as the nominate subspecies. Resident and Bigg’s killer whales have been recognised in the past as un-named subspecies, and were listed in previous versions of the list […].” (Society for Marine Mammalogy, 9 September 2024)

Scientific controversies and future of orca species research

Despite the extensive genetic differences, the scientific community is still reluctant to classify the orcas as separate species. The annual report of the Society for Marine Mammalogy’s Taxonomy Committee (2024) emphasised that killer whale taxonomy remains a subject of intense research:

“Although Morin et al. (2024) proposed their recognition as distinct species of killer whales, such proposal was not followed by the Taxonomy Committee because there were concerns whether this represents a species- or subspecies-level designation. The reasons were mainly due to (1) a possible episodic gene flow among the ecotypes, and (2) the need to conduct a more comprehensive comparative analysis on a global scale to better understand how distinct these ecotypes are from other Orcinus orca clades.

“Therefore, pending further investigation to better evaluate the taxonomy of the eastern North Pacific killer whales, the two ecotypes are considered provisionally as distinct subspecies of Orcinus orca and named following Morin et al. (2024).” (Society for Marine Mammalogy, 9 September 2024)

Efforts are underway to adapt the classification as soon as there is sufficient evidence to distinguish the species clearly. Still, these developments suggest that other undiscovered ecotypes exist in different oceans, which could be classified as separate subspecies and, in the best case, as separate species. This, in turn, would make a significant contribution to preserving biodiversity in the oceans.

Source: NOAA Fisheries, Credit: Merlin Smith

Significance for species conservation

The formal species distinction between the ecotypes of orcas has far-reaching consequences for nature conservation. Each group plays a unique role in its ecosystem: while the Residents help regulate fish populations, the Bigg’s killer whales contribute to controlling marine mammal populations.

Overfishing and habitat loss are a particular threat to the Resident Orcas, which depend on stable salmon stocks in the Pacific. Elsewhere in Spain, Resident Orcas depend on tuna populations. Recognising these groups, possibly even as separate species, could lead to more specific conservation measures tailored to the needs of each group.

Conclusion

Realising that the “Resident” and “Bigg’s” killer whales can be considered distinct subspecies or species represents a significant advance in marine biology and conservation. The differentiation emphasizes the remarkable diversity within killer whales and underscores the urgency of improving their protection.

In addition to the orcas of the Pacific coast, this type of research could also be applied to the Iberian Orcas living in the Atlantic. Like the Pacific Residents, the Iberian Orcas also show specialised and communicative social and hunting behavior.

If future genetic studies reveal a similar differentiation from other orca groups in the Atlantic, it could lead to a reassessment of the conservation status of the Iberian Orcas, which the remaining 35 individuals would urgently need. Until then, it is crucial to protect the habitats and food sources of these unique marine mammals.