The Strait of Gibraltar is one of the most extraordinary habitats for fish and marine mammals in the world. It connects the Atlantic Ocean with the European Mediterranean Sea and separates the two continents of Europe and Africa, more precisely it separates Spain and Morocco.

At its narrowest point, it is only 13 kilometres wide and has a length of 58 kilometres. Due to its unique connection to European coasts, it is one of the busiest waterways in the world.

What makes the Strait special?

The Strait is also exceptional because of its underwater mountain range, which is on average 350 metres below sea level, but also has abysses up to 1,500 metres. From a geological point of view, this connection between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean is also called the Gibraltar Threshold.

Every second, more than one million cubic metres of water flow from the Atlantic Ocean through the strait into the Mediterranean Sea. Slightly less flows back from the Mediterranean into the Atlantic.

The flow into the Mediterranean Sea is its only water supply except for access to the Red Sea via the Nile.

The Mediterranean Sea itself has very high evaporation, about 1-1.4 metres per year. If there were no compensation by the strong surface flow of the Atlantic, the Mediterranean would dry up within the next 2,000 years.

Due to the high evaporation, the water in the Mediterranean Sea is significantly saltier and therefore heavier.

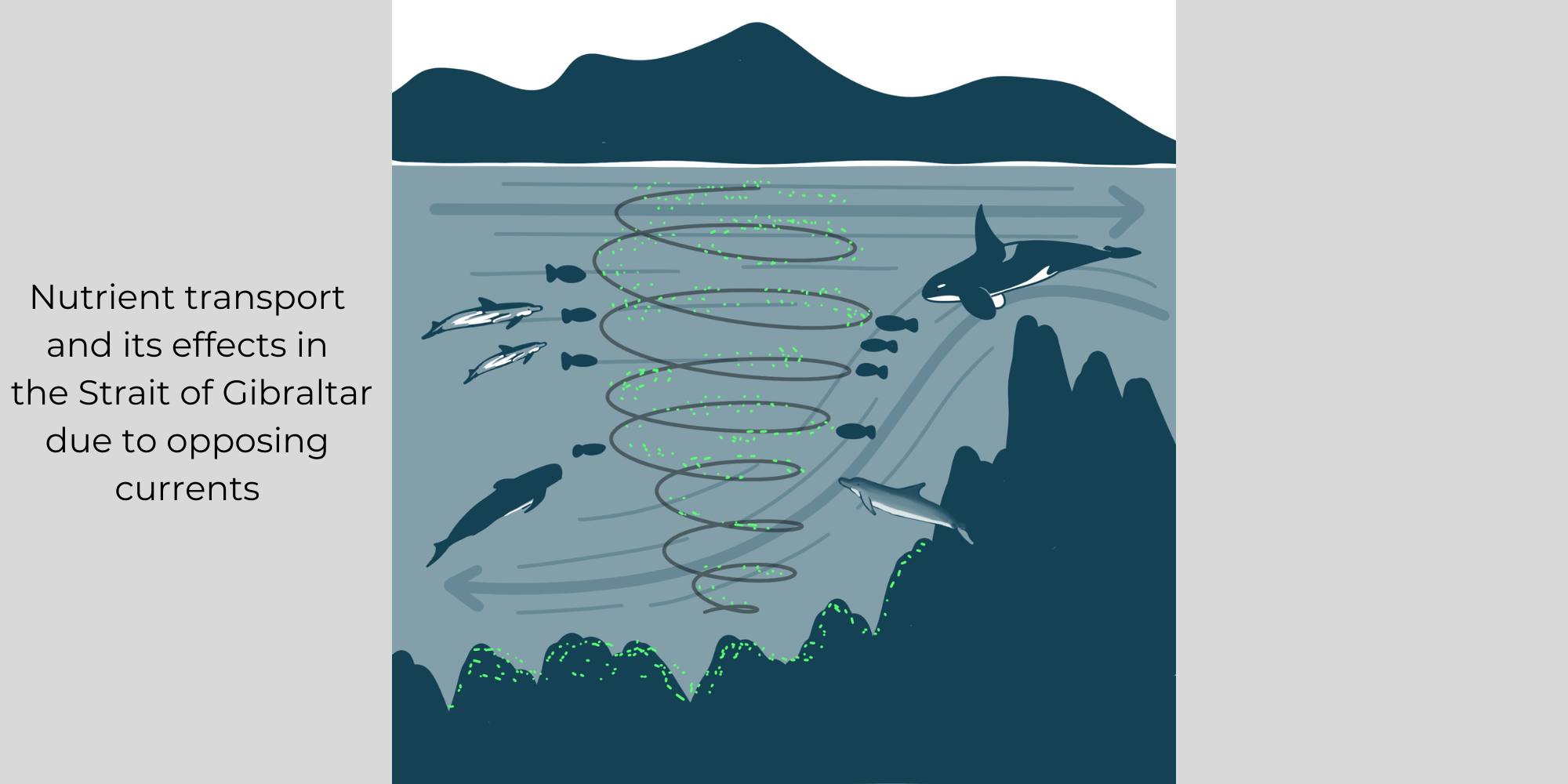

When it flows back into the Atlantic, it sinks and moves as a deep current through the strait, along the underwater mountains. The resulting opposing currents bounce against the underwater mountains, creating turbulence that in turn stirs up nutrients from the ocean floor.

Rich habitat for plants and wildlife

These nutrients are what make the Strait of Gibraltar such a diverse habitat for plants and wildlife. They feed the phytoplankton population, which is so vast in the strait that it can even be viewed from space.

The phytoplankton in turn serves as a food source for the zooplankton, which serves as a nutrient for fish, and the fish populations in the Strait of Gibraltar feed the dolphins and whales.

This large food supply, which is naturally maintained by the opposing currents, ensures that whales and dolphins stay in the Strait of Gibraltar despite the high noise levels.

Whales present in the Strait

In addition, animals often migrate from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea through the Strait in order to reproduce in a protected environment.

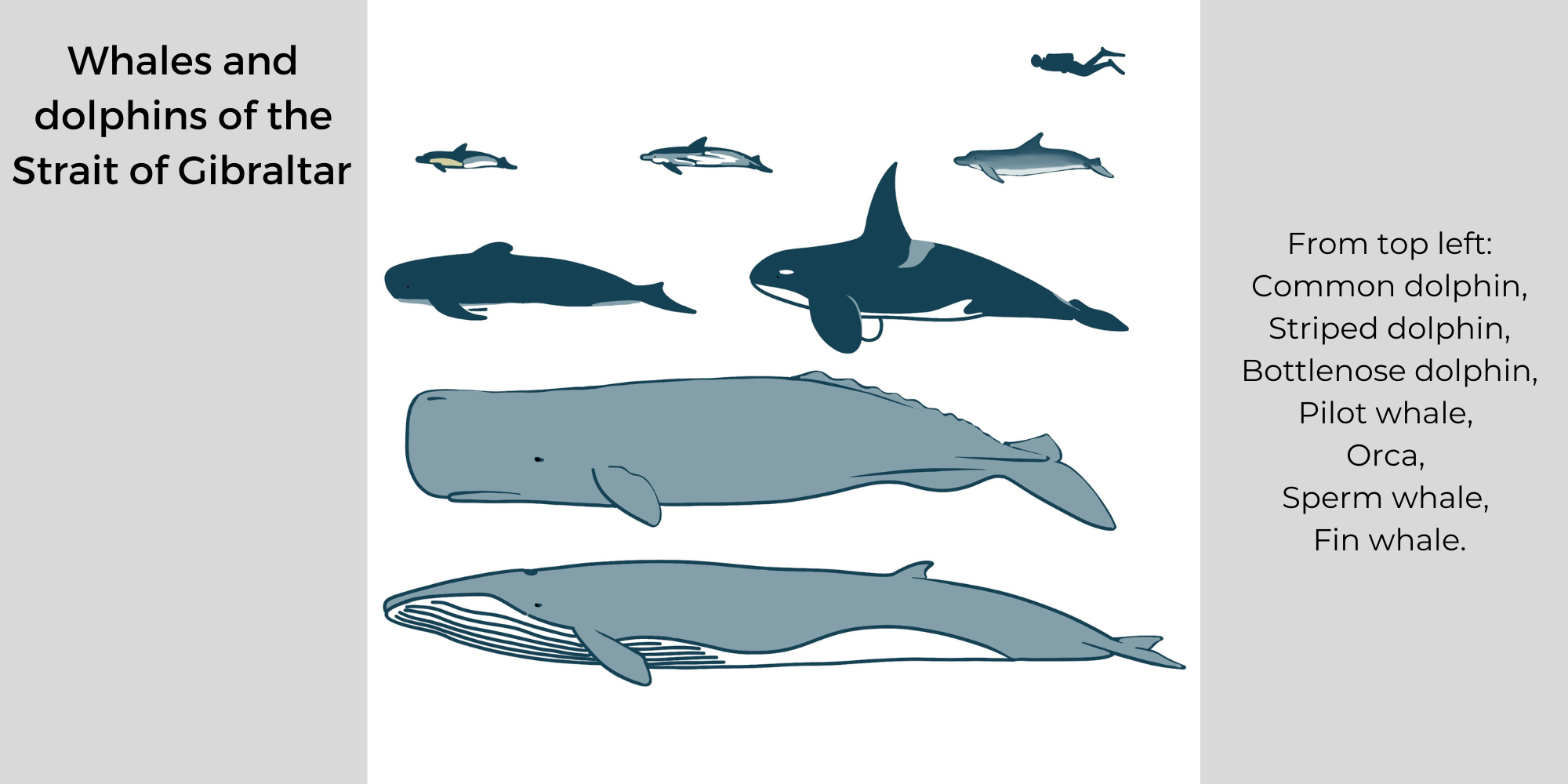

This is true, for example, of the fin whale (Lat. Balaenoptera physalus), but also of the tuna, which swims to the Mediterranean in early summer to lay eggs. Tuna is fished both when migrating into and out of the Mediterranean, and the latter in particular is heavily controlled to maintain tuna populations.

The fishing of the tuna also attracts a resident group of orcas (Lat. Orcinus orca) during the summer months between June and August, which take advantage of the fishermen’s fishing techniques and eat the tuna directly from the hooks.

The relationship between the animals and the fishermen is correspondingly tense and, depending on the yield of the catch, also repeatedly leads to violent outrage of fishermen.

Sperm whales (Lat. Physeter macrocephalus) are also native to the Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean Sea. The resident animals use the depths of the strait to dive for giant squid and calamari.

Because sperm whales are toothed whales and, unlike baleen whales, actively snatch at their prey, they are at the mercy of the heavy plastic pollution in the Strait of Gibraltar.

Accordingly, plastic residues are increasingly found in the stomachs of the animals, which can be traced back to the inadequate infrastructure for waste collection and disposal on the coasts of the Strait.

In addition to fin whales, orcas and sperm whales, pilot whales are also at home in the Strait of Gibraltar. The common pilot whale (Lat. Globicephala melas) or pilot whale is often found in the Strait of Gibraltar. It is a medium-sized toothed whale that can grow between four and six metres long and weigh 1.8 to 3.5 tonnes.

Pilot whales have an estimated life expectancy of 60 years, also feed on squid and fish, and like bottlenose dolphins, can reach speeds of up to 35 km/h. On rare occasions, mixed schools of pilot whales and bottlenose dolphins (Lat. Tursiops truncatus) are seen hunting together in the Strait of Gibraltar.

Dolphins present in the Strait

The bottlenose dolphin, one of the best-known dolphin species through movies such as “Flipper” but also through dolphinaria, can grow between two and four metres long, reaching a body weight of up to 650 kg.

Its life expectancy is similar to that of striped dolphins at about 50 years and they feed like the common dolphin mainly on fish and squid, where they can eat up to 36 kg per day.

In the wild, bottlenose dolphins can reach a speed of 35 km/h and dive for up to 20 min. Bottlenose dolphins can travel about 150 km per day.

The smallest dolphin in the Strait of Gibraltar is the so-called common dolphin (Lat. Delphinus Delphis). In total, common dolphins can grow between 1.7 and 2.4 metres long, reaching a weight of up to 130 kg.

The life expectancy of the animals is up to 40 years. In the Strait of Gibraltar, common dolphins are often found in mixed schools with striped dolphins.

As the name suggests, common dolphins were originally very common. Especially in the Mediterranean Sea they are now highly endangered, which is due to intensive human use in shipping, sewage and fishing or restriction of their food sources in coastal regions.

However, mothers and young common dolphins in particular prefer nearshore waters, as they offer some protection from sharks and other predators, which makes them even more vulnerable to pollution.

Finally, there is the striped dolphin (Lat. Stenella coeruleoalba). It is also known as the blue and white dolphin and, unlike the common dolphin, is still quite abundant in the Strait of Gibraltar.

It can weigh up to 150 kg and can reach a length of up to 2.5 metres. Its life expectancy is about 50 years.

Similar to the common dolphin, striped dolphins feed on fish and squid, but also eat crustaceans. The average daily food intake of a striped dolphin is 10 to 15 kg.

Summary

- The Strait of Gibraltar as a unique, nutrient-rich habitat for large fish populations (e.g., tuna), plant life, and resident whales and dolphins, despite the high volume of shipping traffic

- Special features: opposing currents from the Mediterranean and Atlantic Oceans and deep-sea mountains cause nutrients to be stirred up from the bottom of the Strait

- The whales and dolphins in the Strait of Gibraltar: the common dolphin, the striped dolphin, the bottlenose dolphin, the pilot whale, the orca, the sperm whale and the fin whale

What can we do?

- Raise awareness about the Strait of Gibraltar as a special habitat due to its geographic features

- Reduction of shipping and the associated noise pollution in the strait

- Limitation of fishing of the populations in the Strait of Gibraltar

- Protection of the resident species both from the plant, algae and animal kingdom