Whales and dolphins belong in the wild, where they can live their natural lives. Here are just five ways that captivity impacts the lives of whales and dolphins and why it is cruel:

It’s completely against their natural behaviour

Dolphins and whales are highly intelligent and social animals who have evolved to travel great distances in the wild and find their own food. Orcas, for instance, travel an average of 65 kilometres a day though they have been documented to travel as much as 140 kilometres daily in the wild.

Being stuck in a tank, whales and dolphins don’t get to exercise as much as they are capable of and need to, are completely dependent on humans for food, and don’t have any autonomy over where they travel to or what they do every day.

Captivity affects cetacean health

Being kept in captivity has been shown to affect the long-term health of whales and dolphins. A study in 2017 found that a quarter of all orcas in captivity in the U.S. have severe tooth damage and 70% had at least some damage to their teeth. This damage usually occurs because captive orcas persistently grind their teeth on tank walls, out of frustration, boredom or stress (or all three).

Skin problems, ulcers, appetite loss and sunburn are also common health problems. Dorsal fin collapses happen regularly to orca held in captivity.

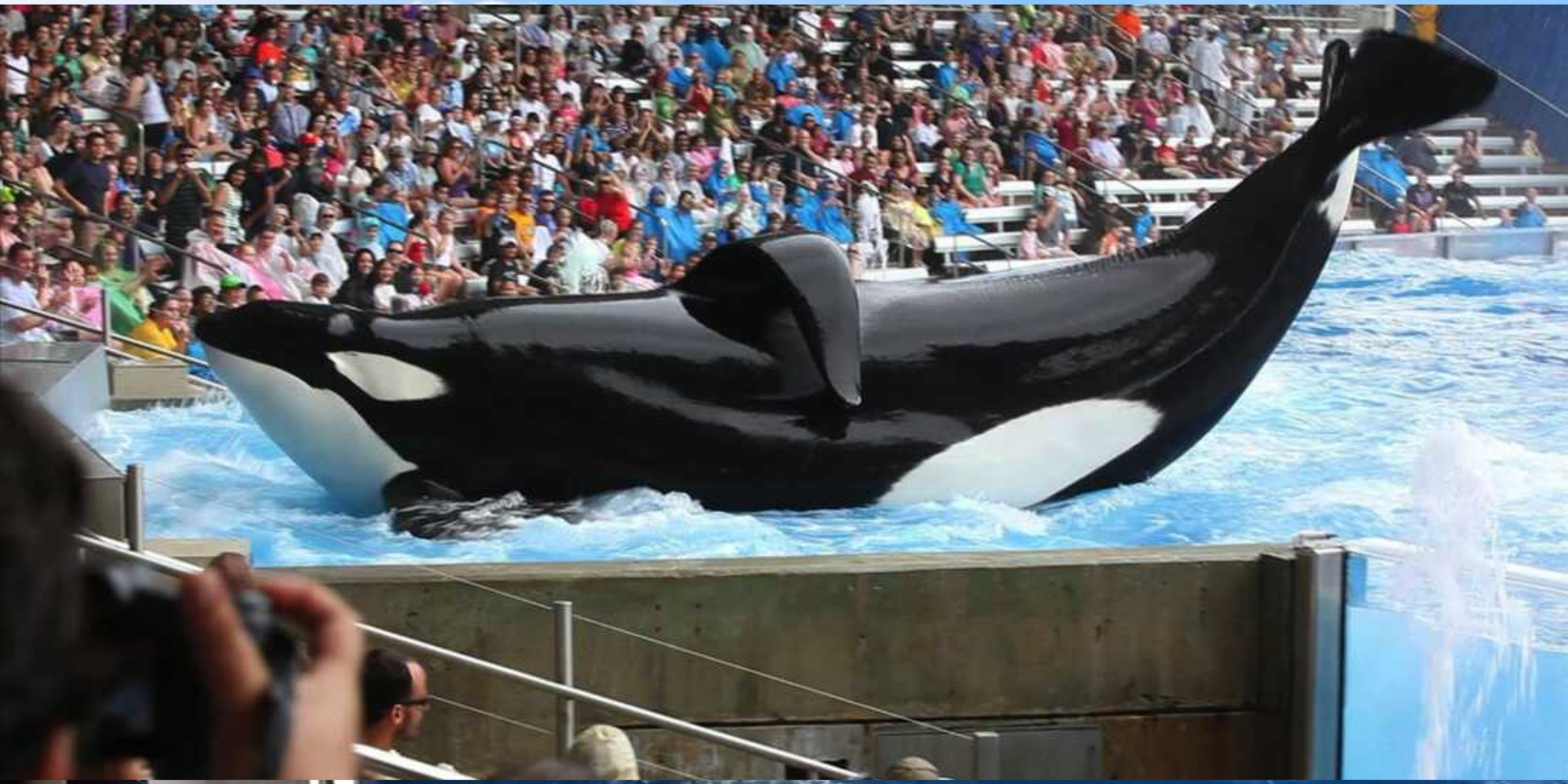

The psychological effects of being kept in captivity on whales and dolphins have long been documented, with cases such as Tilikum (the orca kept in SeaWorld and the focus of the documentary Blackfish) showing how devastating the impacts can be.

Tilikum at SeaWorld Orlando

Captivity reduces the life span of cetaceans

Several studies have shown that whales and dolphins living in captivity have shorter life spans than their contemporaries in the wild.

Research by zoology student Grace Long, while on placement with Whale and Dolphin Conservation in 2018, used data from the Ceta-Base website. She found that the average survival time in captivity for all bottlenose dolphins who lived more than one year was 12 years, 9 months and 8 days. This was much less than the wild where they live to between 30 and 50 years.

The research also showed that 52% of bottlenose dolphins successfully born in captivity don’t survive past one year, a higher mortality rate than the wild.

Animal campaigners and some scientists argue that dolphins can take their own lives. Lori Marino, a behavioural neuroscientist, dolphin expert and Executive Director of The Kimmela Center for Animal Advocacy, published a paper on the subject.

She writes that dolphin’s brains have “sophisticated capacity for emotion and the kinds of thinking processes that would be involved in complex motivational states, such as those that accompany thoughts of suicide.”

The death rate for captive orcas is 2.5 times higher than in the wild (as published in Marine Mammal Science).

Captivity affects social bonds

Whales and dolphins have complex social bonds and are used to interacting with many other individuals in their species (and sometimes also with other species). Being stuck in a tank either by themselves or with only a couple of other animals is incredibly isolating, monotonous and unfulfilling.

Just think of Tokitae who spent most of her life on her own in a cramped tank in the Miami Seaquarium. We can only imagine how lonely this highly intelligent social being felt all those years.

And, of course, if animals in captivity don’t get on with each other (not helped by the close quarters they live in), it can cause tensions, aggressions and physical harm.

Tokitae in her tank in Miami Seaquarium. Photo: Drones for Animal Defense

The process of capture is cruel and can cost lives

Taking whales and dolphins into captivity by force is a cruel process – separating them from family and causing physical distress and mental pain. Sometimes, there is associated loss of life when animals are being captured – Taiji in Japan is a good example of this.

The drive hunt of dolphins takes place every year from September to March in the cove in Taiji (made famous in the documentary The Cove). Large numbers of dolphins are driven to the shore – some are selected for live trade to aquariums and marine parks whilst others are slaughtered for their meat.