New merchandise, featuring three new whale and dolphin species, is launched by WeWhale

WeWhale has launched three new merchandise lines, just in time for Christmas!

The T-shirts, jumpers and hoodies depict three species of cetaceans – the Atlantic spotted dolphin, Cuvier’s beaked whale and the Short-finned pilot whale.

These animals are emblematic of our whale and dolphin observation locations – the Atlantic spotted dolphin and Cuvier’s beaked whale are spotted in Lanzarote while the Short-finned pilot whale is a resident species in Tenerife. A tagline below each image of the cetaceans makes people aware of their required protection and certain abilities.

The locations, Lanzarote and Tenerife, are also reflected inside the designs, which have been beautifully created by ocean artist Rachel Brookes. WeWhale’s collaboration with Rachel has also included our Iberian Orca merchandise line and she created the amazing orca image on our Save the Iberian Orca vessel.

100% of the profits generated from WeWhale merchandise go directly to whale and dolphin protection projects. With every purchase customers make, they are contributing to the conservation of these magnificent animals and their habitat.

The new range is now available on the WeWhale website at wewhale.co/shop. Get it before it’s gone!

Deep dive…into Atlantic white-sided dolphins

A highly sociable species, the Atlantic white-sided dolphin is often spotted in large pods containing hundreds of dolphins.

Its name comes from a distinctive white stripe on its side, which begins just below the dorsal fin and turns into a yellow/ochre stripe that continues towards the flukes. The rest of their colouration is grey and they measure up to 2.8 metres in length.

Atlantic white-sided dolphins are quite stocky with a relatively large dorsal fin and short beaks (with a dark upper and white lower lip). They also have a distinctive black eye ring that extends as a thin line to their upper jaw. Also from this eye ring, a thin line goes to their external ear.

Whilst some other dolphins like to show off, this species is a little more shy overall. They can be seen performing breaches and impressive leaps, tail slapping, and are occasionally spotted bow-riding boats.

They’re nimble swimmers and are sociable with other species, often seen with white-beaked dolphins, bottlenose dolphins, pilot whales and even larger cetaceans such as humpback whales and fin whales.

Where do Atlantic white-sided dolphins live?

These dolphins are found in both temperate and cold waters of the North Atlantic Ocean, usually on the edge of the continental shelf and in canyon waters. As they favour deeper water, they aren’t seen close to the shore that often.

It’s thought that their habitat changes slightly depending on the distribution of their prey species.

Coasts around the world where they are spotted include the U.S. and Canadian east coasts, Ireland, the UK, Iceland, Norway and East Greenland.

What do they eat?

Atlantic white-sided dolphins eat a variety of prey including herring, cod, mackerel, shrimp, hake and squid. They work together as a group to herd fish into larger groupings where they can be picked off easily.

They are sometimes spotted scavenging near fishing trawlers or around where whale species are feeding. On average, their dives last less than a minute but there have been individuals spotted holding their breath for almost five minutes.

Threats to Atlantic white-sided dolphins

Entanglement

Getting caught up in fishing fear is one of the main threats to Atlantic white-sided dolphins. They are particularly susceptible to becoming entangled in fishing boat’s mid-water trawls.

Entanglement can go on to cause injury, fatigue, comprised feeding and sometimes even death.

Environmental change and pollution

Atlantic white-sided dolphins, like other cetaceans, use noise to communicate and to locate prey. Increased noise pollution from vessels and other human activity interferes with this ability.

Climate change and pollution are a threat to all whales and dolphins because of the loss of habitat as waters become warmer.

Plastics and micro plastics, along with chemical pollutants, entering into the water system are a serious threat to all creatures in our ocean.

Hunting

Atlantic white-sided dolphins are hunted in the Faroe Islands and Greenland. In September 2024, 130 individuals were slaughtered during a grindadráp in the Faroe Islands.

You can read more about it in this article from OceanCare, which also mentions a large kill in 2021 when 1,400 Atlantic white-sided dolphins were killed in one day.

WeWhale receives sustainable nautical tourism award

We are delighted to have received an award at the inaugural Gala ‘La Náutica Sostenible en Espańa’, organised by Asociación Nacional de Barcos Eléctricos (ANBE).

The awards took place at the stunning Centro Pompidou de Málaga in Spain.

WeWhale’s award recognises our work of ‘Marine Decarbonisation and Energy Transition within the Scope of Sustainable Nautical Tourism’.

It was an honour for us to gather at the awards ceremony with so many people in the field of sustainable nautical tourism, all committed to making a positive impact for our blue planet.

Founder of WeWhale, Janek Andre, said, “We are proud to be recognised for our commitment to protect the oceans, protect whales and dolphins, and be part of a movement that prioritises sustainability in tourism.”

Thanks to our team member, Marien Huertas Castro, for receiving the award for WeWhale and to ABNE for fostering a community of like-minded organisations working towards a more sustainable future for nautical tourism in Spain.

The WeWhale Pod Episode 18 - Dan Jarvis

Our guest in this WeWhale Pod episode is Dan Jarvis, Director of Welfare and Conservation with British Divers Marine Life Rescue (BDMLR).

Dan talks about moving to Cornwall and how this influenced his interests and career.

He also explains the origins of BDMLR and how it expanded from focusing on seal rescues in its early days to also coming to the aid of stranded or entangled whales, dolphins and porpoises. The organisation is an NGO and has 2,500 trained volunteers.

Dan also shares the story of how a northern bottlenose whale turned up in the river Thames in London in 2006 and the subsequent rescue attempt that BDMLR and other organisations were involved in which gained huge media attention.

He also talks about how welcome it is that more research is being carried out into stranded animal welfare, and his hope that we will see better legal protection for marine mammals.

Find out more about the work of British Divers Marine Life Rescue.

Take a listen to the episode below:

Thanks to Skalaa Music for post-production.

‘Save the Iberian Orca’ campaign features on Germany’s biggest science TV show

Galileo, German’s biggest science TV show, has broadcast a segment on the ‘Save the Iberian Orca’ project, which is a cooperation between WeWhale and Sea Shepherd France.

The piece provides an in-depth look at the Iberian orcas, particularly their unique interactions with boats in the Strait of Gibraltar. It delves into why this specific region is important for them, discussing their migratory patterns and the environmental conditions that attract them.

It also highlights the challenges posed by orca-boat interactions, including potential risks for both the animals and humans.

The broadcast piece also features Janek Andre and the WeWhale team, who are working to mitigate these issues through research and conservation efforts under the ‘Save The Iberian Orca’ campaign.

Their goal is to protect the orcas while promoting peaceful coexistence between orcas and human activities in the Strait. WeWhale’s initiatives, in collaboration with Sea Shepherd France, include educational outreach, encouraging responsible boating, and supporting research that seeks to understand the behaviour of these remarkable creatures.

The team aims to promote awareness about orcas’ natural behaviour and preserve their environment, ensuring that future interactions between boats and orcas are safe for all involved.

Check out the piece here:

Good News Stories about Whale Populations

Commercial whaling, which took place over centuries, had a devastating impact on whale populations globally. Some species nearly went extinct and it is only since the International Whaling Commission’s moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986 that we have seen whale species begin to build back their numbers.

We’re by no means out of the woods as whales face an increasing range of threats. These include ship strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, climate change, environmental and noise pollution, and reduction in their food sources. There’s a huge amount of work still to be done to protect these amazing animals.

But in recent times, there have been several good news stories about whale population increases around the world – always a good thing in our book! Read on to find out more.

Minke whales in Scotland

The Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust has run a 20-year monitoring programme in the waters off Scotland’s west coast. This area is an important habitat for whales, dolphins and harbour porpoises as well as the globally endangered basking shark (the world’s second largest fish).

Sighting rates of minke whales increased to 1.57 per 100 kilometres in the 2023 monitoring programme, the highest in the two decades of records. In total, 167 minke whales were observed during the year.

An interesting feature of the programme is that when sighting rates for minke whales are high, they are low for basking sharks and vice versa. It’s thought there may be a possible association between these two species that causes this. In 2023, the rates for basking sharks fell to 0.07 sightings per 100 kilometres, the lowest recorded by the Trust since it began monitoring.

The charity says the reasons for the changes – and possible association – aren’t yet known and more work is needed to investigate potential causes.

Humpback whales (particularly in Australia and Brazil)

These magnificent whales were heavily targeted and hunted by whalers. By 1986, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species had humpback whales designated as ‘Globally Endangered’. They are now listed as ‘Least Concern’ with population trend increasing.

Thankfully, international restrictions on commercial whaling have allowed humpback whale populations to bounce back. A recent International Whaling Commission assessment of southern hemisphere humpbacks estimated that overall numbers were at around 70 per cent of the number of whales thought to live in that region before hunting began.

Humpback whales in the southern hemisphere spend part of their year feeding at the Antarctic and then swim to warmer waters off the coasts of countries such as Brazil and Australia, where they mate.

Rio de Janeiro is one of the sighting points for the humpbacks on their migration back north. The number of whales being spotted is on the increase, along with more whale watching companies coming into operation.

Find out more in this article, Humpback Whales Majestic Comeback in Rio de Janeiro.

In Australia, experts say that the humpback population on the east coast of the country has reached record numbers.

Wally Franklin from the Oceania Project has said, “We know that population has reached 40,000 or more. We believe the numbers are now getting close to what we call carrying capacity, when the number of whales born equals the number of whales that die of natural causes each year.”

More female sperm whales being found off Irish coast

A new study on sperm whales off the Irish coast has found females and their calves are swimming in higher latitudes than before. In the past, only male whales were found off Ireland with just one ‘stray’ female recorded in Irish waters by commercial whalers in 1910.

The research, from the Marine and Freshwater Research Centre in Atlantic Technological University, shows female and young sperm whales off Ireland have increased over the past decade.

The activity of the deep-diving whales was followed from their traditional breeding grounds near the Azores, in the middle of the Atlantic, to where male sperm whales traditionally feed in Norway.

The reasons why there are more sperm whales being spotted at higher latitudes are not confirmed but may be linked to climate change.

Sperm whales, which are the largest of the toothed whales, were heavily hunted during the commercial whaling period. They went from a population of 1.1 million globally to an estimated 360,000 today.

Antarctic blue whale population shows signs of recovery

Antarctic blue whales paid a heavy toll under commercial whaling – only a few hundred were left after centuries of being hunted.

But new research by Australian scientists and international colleagues suggests that the population is recovering.

Acoustic survey for marine mammal sounds were carried out by deploying sonobuoys along ship tracks during Antarctic voyages from 2006 to 2021. Researchers collected thousands of hours of audio, including whale song and communication.

Over time, blue whales have been heard more and more on the recordings. This suggests that population numbers are steadily increasing.

“When you look back to before this work was started by the Australian Antarctic Division, we really just had so few encounters with these animals – and now we can produce them on demand,” Brian Miller, the senior research scientists on the project told The Guardian.

“We can tell you where they’re frequenting; we can tell you that we’re hearing them more often. So that’s progress.”

Deep dive...into Harbour porpoises

Compared to other porpoises and their dolphin cousins, the harbour porpoise is relatively small. The species has a rounded head with no beak and distinctive spade-shaped teeth.

Its body is robust and stocky, and colouring is dark brown on the back and a paler grey or white underneath that blends in half way along its sides. It also has a small dorsal fin just past the centre of its back.

The harbour porpoise gets its name because it is usually found close to shore in shallow waters (hence the ‘harbour’ part). The word porpoise comes from an unflattering source – it is the Latin word for pig.

The harbour porpoise does emit a sneeze-like puffing sound when it breathes, not unlike a pig’s snort! They are sometimes called by a nickname, ‘puffing pig’.

Four subspecies of harbour porpoise have been recorded: one in the North Atlantic, one in the eastern Northern Pacific, another in the Black Sea and one more in the western North Pacific. A further subspecies has been proposed for harbour porpoises living around the Iberian peninsula and north Africa.

The species is a little shy but is very active and needs to feed continuously to provide the energy needed for its speedy swimming. Harbour porpoises are often spotted on their own in small groups (most commonly a mother and calf group). They tend to surface quickly and don’t show much of their body above the water.

On average, they weigh in around 55-70 kilograms and measure around 1.5 to 2 metres in length. Their average lifespan is 20 years, a little shorter than some other porpoises and dolphins.

Where do Harbour porpoises live?

As mentioned, there are four subspecies of harbour porpoise located in different oceans and seas around the world. Generally, though, most of them are found in the North Atlantic and North Pacific.

They are usually spotted visiting estuaries, shallow bays and tide channels though they are also observed swimming up rivers from time to time.

Their global population is estimated at over a million individuals. They are classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. However, there are concerns about the Black Sea population (listed as Endangered) and also the population around the Iberian peninsula.

Check out this underwater footage of curious harbour porpoises:

What do they eat?

Harbour porpoises have a high metabolism. They need to eat often and to take in calorie rich prey such as herring, anchovies, whiting, sprat and sand eels. They also seek out squid and octopus when they can.

Threats to Harbour porpoises

Entanglement

One of the main threats to harbour porpoises is, unsurprisingly, entanglement in fishing gear. This can go on to cause injury, fatigue, compromised feeding, and sometimes even death.

Vessel strikes

Harbour porpoises are at risk of vessel strikes throughout their range but the threat is higher in areas with busy ship traffic.

Environmental change and pollution

Climate change and pollution are a threat to all whales and dolphins because of the loss of habitat as waters become warmer.

Plastics and micro plastics, along with chemical pollutants, entering into the water system are a serious threat to all creatures in our ocean.

Harbour porpoises, like other cetaceans, use noise to communicate and to locate prey. Increased noise pollution from vessels and other human activity interferes with this ability.

Hunting

Harbour porpoises are hunted off the coasts of Greenland and South Korea, as well as in several other countries around the world.

The WeWhale Pod Episode 17 - Podcast Panel on Combatting Ghost Gear

This special panel episode of The WeWhale Pod focuses on the problem of ghost gear in our waters and ways to combat it.

Our guests are:

- Harry Dennis and Gavin Parker, co-founders of Waterhaul, a social enterprise based in Cornwall in the UK that recycles abandoned marine nets into high quality products

- Sophie Lewis, Interim CEO of the World Cetacean Alliance

- Tom Mustill, biologist turned filmmaker and author of How to Speak Whale: A Voyage into the Future of Animal Communications. Tom is also an Ambassador for the World Cetacean Alliance.

The panel chats about what ghost gear is and how it affects whales and other wildlife all over the planet. Every year, hundreds of thousands of cetaceans are trapped in ghost gear — lost or discarded fishing equipment that drifts through our oceans like a deadly web.

The guests also discuss the process of disentanglement and how changes in the fishing industry (namely a move to plastic gear in recent decades) have contributed to the global problem of ghost gear.

In September 2023, a humpback whale became entangled in fishing gear in Algoa Bay, South Africa, and was fighting for his life.

Thankfully, after a rescue operation, he was freed and able to swim away. The ghost gear was recovered and through collaborative links with the World Cetacean Alliance, made its way to Waterhaul, which saw an opportunity to create something unique from this near-tragedy.

A limited range of sunglasses, made from this recovered ghost gear, is available to purchase. You can check them out, along with more about the rescue operation, on the Waterhaul website. And learn more about the World Cetacean Alliance.

Take a listen to the episode below:

Thanks to Skalaa Music for post-production.

Dolphins That Made a Mark on the World: Fungie

We take a look at Fungie, a bottlenose dolphin living in Dingle, Ireland, who featured in news headlines and captured the hearts of people both there and around the world.

How Fungie’s story began

Back in 1983, a male Atlantic bottlenose dolphin was first noticed off the Kerry coast in Ireland.

The Dingle Harbour Lighthouse Keeper, Paddy Ferriter, began watching this lone wild dolphin as he escorted the town’s fishing boats to and from the harbour.

He had no pod of his own and stayed close to the harbour most of the year. This is relatively unusual for dolphins, who are social creatures and don’t tend to stay living in one place all the time.

The local fishermen enjoyed the company of this dolphin and gave him the name ‘Fungie’ (pronounced Fun-ghee). Over time, he developed from a timid observer of humans into a more playful character.

It wasn’t clear why Fungie was on his own – whether he had become separated from his pod or had struck out on his own. During the following years, he remained on his own, suggesting that he’d easily adapted to this solo dolphin life.

Fungie weighed in at around 500 lbs and measured four metres long. He had some body scars, suggesting he’d had interactions with other dolphins, porpoises or whales. Dingle Harbour, however, was a safe place for him, free of any aggressions with other animals.

Fungie puts Dingle on the map

During the 1980s, word soon spread about this friendly Dingle resident and a local tourist industry cropped up around him. Boat tours regularly took people out into the waters during the summer months. Fungie would come out to meet the boats, jumping high out of the water to the delight of people wanting to take a photo of him. Sea swimmers and kayakers also found Fungie siding up to them to say hello.

As Fungie attracted news headlines in Ireland and around the world, more international visitors came to see him. He was said to put Dingle on the map. Gift shops and pubs in the town took on his name, such was his fame.

Fungie kept up his regular habit of escorting fishing boats out to sea and back. He was also observed playing with small boats and sailing dinghies.

He enjoyed eating salmon and, on several occasions, he was spotted eating a fish commonly known as ‘Garfish’, a species not previously recorded as part of a dolphin’s diet. During winter, he had to travel a little further afield to find food.

Guinness World Record holder

In 2019, Fungie was named in the Guinness World Records as the longest recorded solitary dolphin in the wild. This was given after a report by global charity Marine Connection, which reviewed the world’s documented lone whales and dolphins.

Guinness World Records said that Fungie was estimated to be at least 40 years old.

Fungie disappears

Covid-19 pandemic restrictions in 2020 meant tour boats had to stop bringing groups out to sea. Early on in the pandemic, Jimmy Flannery, who runs Dingle Sea Safari, took it on himself to try and keep Fungie company.

“He craved human interaction, that’s what he lived for,” Jimmy told CNN in a 2021 article.

Tours eventually resumed but in October 2020, it was reported that Fungie had gone missing.

Up to then, he’d never disappeared for more than a few hours at a time so the local community was understandably concerned for his welfare.

Search for Fungie

A search operation got underway with a dozen boats involved. Search and rescue divers checked out coves and inlets where Fungie normally swam and a sonar scan of the seabed was carried out.

There was faint hope when a sighting was reported in the Irish media but it turned out to be another dolphin. As more time passed, it sadly became more unlikely that Fungie would be seen again. It’s thought that he probably died of old age – when bottlenose dolphins die, they tend not to wash up on land.

A memorial was held for Fungie on the one-year anniversary of his disappearance, with boat operators offering free boat trips out to the entrance of Dingle Harbour and local people gathering to remember him. Around 1,000 people turned out to mark the moment.

The Fungie Effect

Fungie made a lasting impression on generations of people and marine biologist Kevin Flannery, who has been observing Fungie since 1983, says he also helped people understand why they should care about the ocean.

“An awful lot of people got educated about the marine world in the realisation that it wasn’t the place where you dump plastic and things, that it was a living entity where you had all these whales, dolphins, cetaceans of all sorts – and it was a place to be taken care of,” he told CNN.

“I suppose in that sense Fungie has educated millions of people,” he added, saying that the dolphin has contributed to a sea change in attitudes around sustainability.

Many of the boat tours that were centred around seeing Fungie have since diversified their tours, offering private trips of the harbour, sea safaris, tours of the nearby Blasket Islands and eco-tours.

Fungie left a lasting impression not only on the people in the local community but the countless people from all over the world who came to see this solitary but playful wild dolphin.

Captivity is cruel – why dolphins and whales shouldn’t be kept in captivity

Whales and dolphins belong in the wild, where they can live their natural lives. Here are just five ways that captivity impacts the lives of whales and dolphins and why it is cruel:

It’s completely against their natural behaviour

Dolphins and whales are highly intelligent and social animals who have evolved to travel great distances in the wild and find their own food. Orcas, for instance, travel an average of 65 kilometres a day though they have been documented to travel as much as 140 kilometres daily in the wild.

Being stuck in a tank, whales and dolphins don’t get to exercise as much as they are capable of and need to, are completely dependent on humans for food, and don’t have any autonomy over where they travel to or what they do every day.

Captivity affects cetacean health

Being kept in captivity has been shown to affect the long-term health of whales and dolphins. A study in 2017 found that a quarter of all orcas in captivity in the U.S. have severe tooth damage and 70% had at least some damage to their teeth. This damage usually occurs because captive orcas persistently grind their teeth on tank walls, out of frustration, boredom or stress (or all three).

Skin problems, ulcers, appetite loss and sunburn are also common health problems. Dorsal fin collapses happen regularly to orca held in captivity.

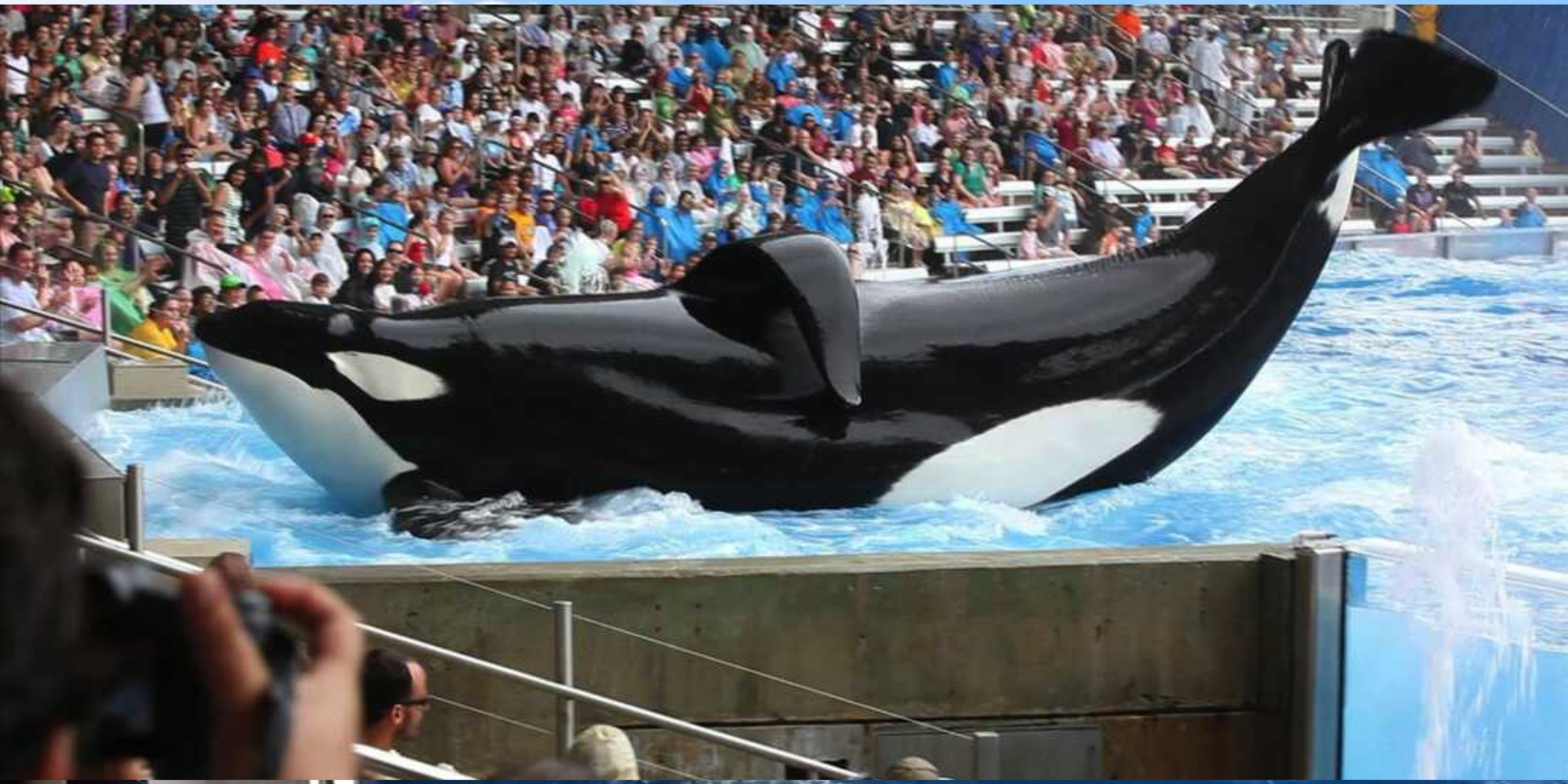

The psychological effects of being kept in captivity on whales and dolphins have long been documented, with cases such as Tilikum (the orca kept in SeaWorld and the focus of the documentary Blackfish) showing how devastating the impacts can be.

Tilikum at SeaWorld Orlando

Captivity reduces the life span of cetaceans

Several studies have shown that whales and dolphins living in captivity have shorter life spans than their contemporaries in the wild.

Research by zoology student Grace Long, while on placement with Whale and Dolphin Conservation in 2018, used data from the Ceta-Base website. She found that the average survival time in captivity for all bottlenose dolphins who lived more than one year was 12 years, 9 months and 8 days. This was much less than the wild where they live to between 30 and 50 years.

The research also showed that 52% of bottlenose dolphins successfully born in captivity don’t survive past one year, a higher mortality rate than the wild.

Animal campaigners and some scientists argue that dolphins can take their own lives. Lori Marino, a behavioural neuroscientist, dolphin expert and Executive Director of The Kimmela Center for Animal Advocacy, published a paper on the subject.

She writes that dolphin’s brains have “sophisticated capacity for emotion and the kinds of thinking processes that would be involved in complex motivational states, such as those that accompany thoughts of suicide.”

The death rate for captive orcas is 2.5 times higher than in the wild (as published in Marine Mammal Science).

Captivity affects social bonds

Whales and dolphins have complex social bonds and are used to interacting with many other individuals in their species (and sometimes also with other species). Being stuck in a tank either by themselves or with only a couple of other animals is incredibly isolating, monotonous and unfulfilling.

Just think of Tokitae who spent most of her life on her own in a cramped tank in the Miami Seaquarium. We can only imagine how lonely this highly intelligent social being felt all those years.

And, of course, if animals in captivity don’t get on with each other (not helped by the close quarters they live in), it can cause tensions, aggressions and physical harm.

Tokitae in her tank in Miami Seaquarium. Photo: Drones for Animal Defense

The process of capture is cruel and can cost lives

Taking whales and dolphins into captivity by force is a cruel process – separating them from family and causing physical distress and mental pain. Sometimes, there is associated loss of life when animals are being captured – Taiji in Japan is a good example of this.

The drive hunt of dolphins takes place every year from September to March in the cove in Taiji (made famous in the documentary The Cove). Large numbers of dolphins are driven to the shore – some are selected for live trade to aquariums and marine parks whilst others are slaughtered for their meat.