The WeWhale Pod Episode 1 - Harry Eckman, CEO of the World Cetacean Alliance

We’re delighted to share the very first episode of The WeWhale Pod, a podcast diving into stories beneath our oceans.

Each episode, the WeWhale Pod presents a guest connected to the world of whales, cetaceans and the ocean.

Our guest this episode is Harry Eckman, international animal welfare specialist and CEO of the World Cetacean Alliance.

Amongst the topics, Harry talks to us about his path into working in animal welfare and protection, the varied work of the World Cetacean Alliance, the greatest threats to whales and how we can work together to ensure they are protected and free in our oceans.

Thanks to Skalaa Music for post-production.

Take a listen to the episode below:

Deep dive…into Grey whales

Grey whales (Eschrichtius robustus) make one of the longest annual migrations of any mammal, travelling between 15,000 to 20,000 kilometres.

The baleen whales were once commonly found through the Northern Hemisphere but are now only regularly found in the North Pacific Ocean. There are two populations in this region: the Eastern Pacific grey whale and the Western Pacific grey whale.

The species can weigh up to 40 tonnes (equal to the combined weight of 20 cars) and grow to 15 metres long, making it one of the bigger whales in our ocean. It has a mottled grey appearance with a relatively small narrow head, a robust body and small paddle-shaped flippers.

Instead of a dorsal fin, grey whales have six to twelve knuckles between their hump and flukes, with these knuckles forming a low hump. They’ve small eyes located just above the corners of the mouth.

On first glance and due to their similar size, some people mix up grey whales and humpback whales but there are a few distinctive aspects to the grey whale. These include its heart-shaped blow. And, interestingly, the grey whale has two blow holes whereas other whales, including humpbacks, only have one blow hole.

The whale’s mottled grey appearance (think crusty skin) is due to the large amounts of whale lice and barnacles that attach themselves to the cetacean’s head and body. Parasites attach and later detach in cold feeding grounds, leaving behind scars and patches that are used by scientists to identify individual whales.

A grey whale’s lifespan is generally 50 to 70 years though there is research indicating they may live up to and beyond 75 to 80 years.

Grey whales aren’t highly social as a group and tend to come together during the breeding season and parts of their annual migration.

However, the species has been observed showing curiosity towards boats and approaching them to check out occupants. It’s no surprise then that when whale watching first began in the U.S. in the 1950s, grey whales were amongst the first species that companies focused attention on.

Where do grey whales live?

Grey whales predominantly live in the North Pacific Ocean amongst two population groups. The first population lives along the Pacific coast of North America (usually called Eastern Pacific grey whales or North American grey whales) and the second population group, which is smaller in size, lives in the western part of the Pacific Ocean (around Korea, China and Japan). They’re called Western Pacific grey whales or Asian population grey whales.

The Eastern Pacific grey whale feeds during the summer in the Bering and Chukchi Seas between Alaska and Russia. A small group of “summer resident” whales don’t migrate as far as Alaska to feed during the summer – instead, they do their feeding further down the coast (they’re found off British Columbia, Canada, down to northern California).

In the autumn, these grey whales migrate south along the west coast of the U.S. to the Baja Peninsula in Mexico and the south eastern Gulf of California. In the warm waters, they breed and give birth to calves.

On the other side of the Ocean, the Western Pacific grey whale feeds in the summer in the Sea of Okhotsk (near the northeastern coast of Sakhalin Island in Russia) and also in an area of the Bering Sea (around the Kamchatka Peninsula). In the autumn, the species migrates down to the South China Sea where it breeds.

Research since 2004 has detected some members of the Western Pacific grey whale population migrating to the Pacific coast of North America to visit feeding and wintering grounds used by their Eastern Pacific grey whale counterparts.

Grey whales have been spotted in other areas around the world, prompting scientists to question if they are increasing their geographic spread and/or reverting back to habitats that they lived in prior to their population drop caused by commercial whaling.

A fascinating 2022 EU funded research project Demise of the Atlantic Grey Whale investigated whether the species might eventually return to European waters.

This was also explored by Rebecca Giggs in her book Fathoms: The World in the Whale. She writes, “Grey whales, too, are altering the choreography of their long transportations. Grey whales are leaving the North Pacific and crossing over the top of the globe through the ice-free Northwest Passage to appear in the Atlantic. Grey whales surface now off Israel, Spain, and Namibia, where they have never been recorded before.”

In the summer of 2021, a grey whale was spotted off the coast of Morocco and was seen also off the coast of France and Italy.

More is known about the Eastern Pacific grey whale than the Western species but they share the same broad migratory pattern of going from warm to colder waters and back again. They usually migrate for about two to three months annually in large groups and they pace themselves, swimming up to 8 kilometres per hour.

Generally speaking, grey whales stay close to the shore (they rarely venture more than 20 to 30 kilometres offshore) and feed in shallow water.

Population

The grey whale was extensively hunted during the peak years of commercial whaling, almost to the point of extinction. The species was once known as “devil-fish” because they fought back aggressively when attacked by whalers.

It looked like the species was on the right track to recovery having come under the protection of the International Whale Commission ban on commercial whaling in 1986.

In 2016, NOAA Fisheries in the U.S. estimated the size of the Eastern Pacific grey whale population to be nearly 27,000, an increase from previous figures.

However, a new assessment by NOAA released in October 2022 shows that the numbers have decreased in the past six years. The count put the population at 16,650, down 38% since 2016. The whales in the assessment also produced the fewest calves since scientists began counting their births in 1994.

But the Eastern Pacific grey whale population size is still considerably more than the Western population, which has one of the smallest whale populations in the world and is listed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species as critically endangered.

Some estimates state there are around 250 – 300 whales in this population whilst other more conservative estimates put it at 100 individuals remaining.

What do they eat?

Grey whales are bottom feeders, which means they trawl the soft muddy part of the seabed in shallow areas. They use their baleen to sieve out water, leaving the food behind in their mouths.

They consume mostly small invertebrates (plankton, amphipods) along with crab larvae, and are also known to feed on herring eggs and larvae in eelgrass beds. They eat around one tonnes of food each day.

Interestingly, most grey whales turn on their right side when they bottom feed and this means the baleen on the right side is usually shorter and more worn than the baleen on the left side.

Threats to grey whales

Entanglement in fishing gear

Like other whales, grey whales can become entangled in different types of fishing gear. This can cause injury, fatigue, compromised feeding and even death.

Environmental change and pollution

Climate change and pollution can lead to loss of habitat as waters become warmer. Plastics and micro plastics in the ocean pose a threat to whales, along with all other marine mammals and fish. Chemical pollutants entering into the water ecosystem are also a serious threat to all creatures in our ocean.

The grey whale’s summer feeding habitats around Sakhalin Island and the Bering and Chukchi Seas are increasingly being targeted for offshore oil and gas development. These developments disturb whales in terms of underwater noise being generated, water pollution and negative impacts on their feeding behaviour.

Food source reduction

In 2019, NOAA Fisheries in the U.S. declared an “Unusual Mortality Event” or UME for grey whales. This was due to a significant increase in the number of whales washing up on beaches on the country’s Pacific coast (384 cases).

The reasons for these deaths is not fully clear but researchers say factors could have included climate change, its effect on sea ice as well as availability of prey. It was reported that many – but not all – of the dead whales that washed up appeared malnourished or emaciated, prompting questions as to whether their food sources are being reduced.

A 2021 study into the UME examined food scarcity as a potential cause for the rise in skinny whales and said, “[It] could also be due to a decline in prey on their feeding grounds. Benthic amphipods are of great importance to grey whales…comprising 90% of their food intake.”

It’s thought that with less amphipods, grey whales may be turning to krill as a food source and unfortunately it’s not as nutritionally rich for their needs.

A number of these UME cases were found to be caused by vessel strikes.

Vessel strikes

Large ships operating in the North Pacific Ocean pose a threat to grey whales due to vessel strikes. A study published in 2021 showed that large ships operating in the Bering Sea, Gulf of Alaska and along the west coast of North America (where there is a huge amount of commercial shipping routes) all posed a high risk to the species.

It also identified areas in the Russian Far east where vessel strikes pose a significant threat to the whale species.

Natural predators

During northward migrations, grey whale mothers and calves stay close to the shore (usually within 200 metres). This is thought to be an evasive measure to avoid attacks from orcas.

Attacks on grey whales by orcas are not always fatal, in which case the grey whale bears the signs of survival (usually tooth rake scars and disfigurements on their tail flukes).

Humpback whales have been observed coming to the aid of grey whales under attack from orcas. Check out the video below filmed for BBC’s Planet Earth.

Whales That Made a Mark on the World: Migaloo

Picture: Queensland Environmental Protection Agency

In our second blog on whales who’ve captured the attention of the world and the hearts of people, we take a closer look at the humpback whale Migaloo. Famed because of his all-white appearance (he’s a rare albino humpback), he first entered public consciousness back in 1991.

First spotting

A group of volunteers were carrying out a whale count off Byron Bay on Australia’s East Coast in 1991. Imagine their surprise when a white humpback whale was first spotted through a telescope from a distance of more than 5km away. A photo was taken through the telescope and though it turned out to be quite blurry, it was a historic photo capturing a unique moment!

Two years later, Pacific Whale Foundation researchers encountered Migaloo in Hervey Bay, Queensland, and were able to confirm that he was indeed all-white. The Foundation was able to record him singing (a trait that’s distinct to male humpbacks) in 1998.

In 2004, genetic testing of sloughed skin cells by Southern Cross University Whale Research Centre confirmed that Migaloo was, indeed, a male whale.

He is clearly identifiable from his white appearance but he has some other distinctive physical traits – his dorsal fin is slightly hooked and his tail flukes have a particular shape, with spiked edges running alongside the lower trailing side. He is 15 metres in length.

How did he get his name?

From the beginning, the Australian public and the wider world were intrigued by this unusual whale. He needed a name and it was decided that the naming should be done by the elders of the local Aboriginal collective in Hervey Bay.

They named him ‘Migaloo’ or ‘white fella’. In Aboriginal culture, the white or albino colour of animals demonstrates the need to respect all forms of life even if they appear different than ‘normal’. And that they should be honoured with reverence and respect, not discrimination and shame.

What’s Migaloo’s life like?

The whale – who is now estimated to be 33-36 years old – is part of a humpback whale group that feed in Antarctica during the southern hemisphere’s summer and autumn (November – May).

In the corresponding summer and spring (June – October), they migrate up along the east coast of Australia and then breed in the warm waters near the Great Barrier Reef.

Every couple of years, there are sightings of Migaloo as he transits off the Australian coast and he’s also been spotted in New Zealand waters. He has been sighted many times with a pal, a male humpback whale known as Milo.

Australian legislation givens protection to all humpback whales but Migaloo and other humpbacks that are more than 90% white are “special management marine mammals” which gives them extra protection. Boats can’t approach within 500 metres of them and access in the skies above is also restricted. There’s significant fines if these rules are breached.

These measures are to make sure Migaloo is not harassed or can injure himself in a boat collision, such is the human interest in seeing him.

Before the restrictions were brought in, the whale had collided with a trimaran off northern Queensland. It caused some damage to the boat’s keel and its rudder, which people feared might have lodged in the whale’s back.

Fortunately, Migaloo was seen swimming freely in waters just north of where the collision happened. A subsequent examination revealed he had only suffered a slight wound on his back, right of his dorsal fin.

Research on Migaloo

The Pacific Whale Foundation has been able to gather a lot of data about Migaloo sightings over the years (without the use of radio tags, as he is so easily identifiable). This has helped their research work on humpback migratory patterns in the South Pacific.

The Southern Cross University Whale Research Centre, based in Australia, has also collected important research data about Migaloo over the years (particularly through the work of Wally and Trish Franklin).

Is Migaloo the only albino humpback in the world?

For a few years, it was thought that Migaloo was the only whale of his type in the world. But there have since been sightings of white humpback whales considerable distances apart, which supports the idea of him not being unique (although some argue he is unique in the Eastern Australian seaboard).

Three other white humpbacks have been documented in the world (Bahloo, Willow and Migaloo Jr), making them extremely rare.

Migaloo Jr (also known as Chalkie) was a calf when spotted in the Whitsunday Islands in Australia in 2011. He was given his name because of a similarity to Migaloo but isn’t confirmed to be his offspring (only genetic tests can prove this).

The future for Migaloo

On average, humpback whales live 45 to 50 years, though they can live up to 80 or 90 years old.

In July 2022, fears were raised about Migaloo when a dead white humpback whale washed up on a beach in Victoria, Australia. Environment officials were able to test samples from the dead whale and compare to samples they have on file from Migaloo, and were able to determine that the whale was not Migaloo. It was found to be a sub-adult female whale.

Biologists are concerned that Migaloo may develop skin cancer from the sun’s UV rays, something he is more vulnerable to because of his lack of pigmentation. Red marks have been spotted on his dorsal fin in the past, and are being monitored whenever he is spotted.

Migaloo was last seen in June 2020 but it’s quite common for there to be two to three year gaps between sightings, so only time will tell when he next makes an appearance.

He’s certainly a whale that’s beloved by millions of people, as demonstrated by the many social media accounts dedicated to him. And the fact that he has his own website, where people log their Migaloo sightings.

Check out previous blog Whales That Made a Mark on the World: Tokitae (Lolita)

Deep dive...into Sperm whales

There’s still a lot of mystery around sperm whales due to the fact that they spend so much of their life out at sea, far away from land.

Though not the largest species of whale, the sperm whale (Physter macrocephalus) has the largest brain of any animal on the planet. It’s also the biggest species of all the toothed cetaceans.

On average, a male sperm whale grows to 16 metres long with a female growing to 11 metres long. In appearance, the sperm whale is dark grey and has a torpedo shaped body with wrinkled, prune-like skin. Its tail, triangular in appearance, is clearly visible when the mammal swims headfirst into a deep dive.

A sperm whale’s head makes up around a third of its body length and is square-shaped. It has short rounded dorsal fins, and the pectoral fins on either side of their bodies are also relatively small and paddle-shaped.

Along with its block-shaped head, the sperm whale is easily recognisable because of its jaw, containing up to 52 cone-shaped teeth in the lower half of the mouth.

Sperm whales get their name from ‘spermaceti’, the waxy substance found above and in front of the skull (that was much sought after by commercial whalers for use in products such as oil lamps and candles). We don’t fully know the function of this substance but experts believe it may help the whale regulate its buoyancy and/or to focus sound.

The sperm whale is probably best known for the depiction in Herman Melville’s 19th century novel Moby Dick. The writer partially based the whale on a real life albino whale of that period called Mocha Dick who lived off Chile. He was hunted by whalers and managed to survive for years and years, fighting back with considerable ferocity.

Lifespan

On average, a sperm whale can live to 70 years of age, though there is evidence of the species living longer than that.

Sperm whales live in stable and complex matrilineal groups and are often seen in pods of 15 to 20 whales. Male sperm whales usually hang out with the group until they’re in their 20s or 30s, when they tend to go their separate ways. Females usually stick with the group longer and form ‘nursery schools’ to collectively take care of calves and protect them from danger.

Sperm whales when they are born are pretty big! They measure, on average, four metres long. As they can’t undertake the deep dives that their mothers can, they’re taken care of in the ‘nursery schools’ whilst mum is out hunting for food.

Where do sperm whales live?

Sperm whales inhabit the deep ocean and are rarely seen along coastlines except in areas where there are deep trenches or underwater canyons as you get closer to the shore. Kaikoura Canyon in New Zealand is one such place and is an important breeding ground for sperm whales.

The mammals are also spotted in island chains such as the Azores, Galapagos and the Canary Islands, and are seen in the Strait of Gibraltar, between Spain and Africa.

A small population of less than 1,500 sperm whales lives in the Gulf of Mexico. Scientists have discovered they are a distinct population – they’re smaller in size than other sperm whale populations (probably a response to limitations in their food sources) and they use combinations of calls different to other sperm whale populations.

Sperm whale migrations aren’t as well understood as the migrations of baleen whales such as humpback whales. Generally speaking, females and their young are more likely to stay in tropical waters year-round and adult males make long journeys into waters closer to the two polar regions.

What do they eat?

These toothed whales eat around one ton of food a day – feeding on large squid (particularly giant squid), fish, skates and sharks.

The species spends most of its life hunting for its prey, diving deep in order to catch it.

Light becomes limited the further down into the ocean the sperm whales travel so they use their finely tuned echolocation skills to help them find prey.

A sperm whale typically dives to a depth of 1,000 metres though they have been documented diving to 2,000 metres and more (which involves holding their breath for an estimated 1.5 to 2 hours).

It’s no wonder then that they spend time recovering at the surface and taking lots of breaths after they re-emerge from a feeding dive.

Population

Sperm whales were once thought to have numbered 1.1 million worldwide, according to the American Cetacean Society. Their population was decimated by the whaling that occurred in the 18th century right through to the 20th century.

They were a popular target for commercial whalers for a few reasons: 1) spermaceti (waxy fluid contained in their heads that could be used for products such as oil lamps, lubricants, cosmetics and candles), 2) the blubber in their bodies, and 3) ambergris.

The latter is often described as one of the world’s strangest natural occurrences and only occurs in sperm whales. It’s a substance that forms around digested squid beaks in a whale’s stomach. It’s thought to occur so that the internal organs are protected from the sharp beaks.

Ambergris was highly prized by perfumeries as an ingredient, so it was something that whalers were eager to acquire and sell on.

Whaling is no longer a threat to the species and there is evidence that its population is recovering, though it is still a fraction of its previous number. It’s estimated there are now 360,000 sperm whales globally. However, it’s a difficult species to obtain accurate numbers on because it lives so far out to sea.

It’s considered by experts to have vulnerable to endangered status, depending on locality around the world.

Threats to sperm whales

Vessel strikes

All whales are vulnerable to ship strikes, which can injure or kill them. There isn’t a huge amount of documentation available on vessel strikes caused to sperm whales but as vessel traffic worldwide is increasing, the risk of collision increases with it.

Vessel strikes are believed to be one of the main drivers of sperm whale population decline in the Mediterranean and could also be a threat to the survival of sperm whales in the Canary Islands.

Noise

Underwater noise pollution, caused by humans, can interrupt and disturb the normal behaviour of whales. They use sound to communicate so any interruption interferes with that communication and to their ability to pick up signals in the environment.

Entanglement in fishing gear

Like other whales, sperm whales can become entangled in different types of fishing gear. This can cause injury, fatigue, compromised feeding and even death. A technique that sperm whales have developed to remove fish from longline gear may unfortunately contribute to their entanglement.

Depredation is when the whale uses its long jaw to create tension on the fishing line and this shakes fish off the hooks. The whale can become entangled or injured whilst trying to free up food this way. Find out more about depredation in this article in Hakai magazine.

Environmental change and pollution

This can lead to both loss of habitat (as waters become warmer) and lack of food for sperm whales. Changing water temperatures can impact the timing of important cues for whales such as when it’s time to depart to feed or to migrate to breed.

The feeding range of sperm whales is one of the greatest of all species on earth so it’s thought the species is less susceptible to food scarcity than other types of marine species.

Plastics and micro plastics in the ocean pose a threat to whales, along with all other marine mammals and fish. Chemical pollutants entering into the water ecosystem also pose a serious threat to all creatures in our ocean, including sperm whales.

Natural predators

Sperm whales are not regularly the target of natural predators, though there have been observations of orca whales attacking sperm whale pods. Large sharks are also thought to be occasional predators of sperm whale calves

Pods have been seen forming protective circles against potential attacks, positioning any vulnerable young or injured whales in the centre of their defensive formation.

Whales That Made a Mark on the World: Tokitae (Lolita)

Picture: Wallie V. Funk photographs and papers, Center for Pacific Northwest Studies, Heritage Resources, Western Washington University, Bellingham WA 98225-9123

*This blog was updated in August 2023

Over the past 30 years, several whales have captured the attention of the world and the hearts of people when they featured in news headlines. In a series of blogs, we take a look at five whales who’ve made a huge impact and created debates around captivity, rehabilitation in the wild, conservation and whale welfare.

Our first story focuses on a young orca whale, known as Tokitae (or Lolita), taken from Puget Sound in the U.S. more than half a century ago.

Capture

The notorious Penn Cove captures took place on Saturday 8 August 1970 near Puget Sound, Washington State. More than 80 orca were forced into the cove, using speedboats, nets and explosives, with mothers and calves separated. The orca, clearly traumatised, vocalised loudly (video footage of the brutal captures later came to light).

Five whales drowned in the nets and seven orca were removed, sold and transported to various marine parks. One of those orca was four-year-old Tokitae, or Toki (who later came to be known by Lolita, the stage name given to her).

For many years, she was the only surviving orca of the seven taken that August day. She spent 53 years in captivity at the Miami Seaquarium where it’s estimated she performed in more than 25,000 shows.

A life that couldn’t be more different than the one she experienced during her first four years – swimming and foraging for salmon in Puget Sound, surrounded by her close-knit family unit.

Campaigning

Over the years, campaigners consistently raised awareness of Tokitae and her plight, particularly the fact that she lived in the smallest orca tank in the world. At 24 metres long and ten metres wide, her tank was just four times her size.

It’s estimated that she would have needed to circle it 600 times to travel the same distance that a wild orca covers in a single day. It also didn’t allow for a very normal orca behaviour, that of diving.

You may have seen widely shared drone footage from 2014 showing the size of her tank – if not, check out Drones for Animal Defense video on YouTube.

Concerns were raised about Tokitae’s health, including experiencing sunburn from being exposed to the sun and having eye and teeth problems, to name just a couple. Activists say she endured mental and behavioural effects from boredom and isolation – she was the only orca at the Miami Seaquarium (her orca companion for 10 years, Hugo, died in 1980). Some experts say that she remained in relatively good shape considering the length and nature of her captivity.

Supporters, including celebrities and indigenous communities, lobbied for her rehabilitation and release, with the campaign particularly growing momentum since 1995.

Tokitae’s family is a group of 43 orcas, known as L pod who belong to the Southern Resident orca group of 88 whales. They were listed as endangered in 2005, one of the reasons why Miami Seaquarium argued at the time that it was best for Tokitae to stay in her current home.

In February 2015, Tokitae was officially included by the National Marine Fisheries Service in the endangered listing for the Southern Resident orca group.

Critical report

A 2021 report by the United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service cited serious problems during an inspection of Miami Seaquarium. These included poor water flow leading to an increase in bacteria and algae in several tanks and pools, reduction in food quantity, leading to possible malnutrition and dehydration, and potentially placing incompatible animals together resulting in the injuries and/or deaths of cetaceans and pinnipeds.

They were also cited for having insufficient shelter to protect the mammals from direct sunlight, and inappropriate and potentially dangerous routines demanded of Tokitae.

The future for Tokitae

There was some encouraging news in 2022, believed to have been prompted by the report. In March, the Miami Seaquarium, under new management, said they would no longer conduct daily shows featuring Tokitae. Effectively meaning she retired from performing.

The tank was now off limits to public visitors but it still continued to be her home, a space that it was woefully small for an animal of her size. So what could the future hold for Tokitae?

In 2022, she was now thought to be 56, which is very old for an orca in a marine park or aquarium. But not old for an orca in the wild, where female orcas can live well into their 90s.

An L pod matriarch called Ocean Sun, believed to be Tokitae’s mother, is still alive and well at an estimated 93 years of age.

Tokitae continued to vocalise in her native L pod language and it’s believed around 14 of the orca who were in the area with her prior to her capture are still alive. The hope was that she could be rehabilitated in a seaside sanctuary and if communication could be re-established with her pod, that she could be released into the wild with them.

She would have needed to re-learn new skills in the rehabilitative pen, including how to catch her own food, and be given time to build up her strength and stamina once again.

The Sacred Sea Conservancy along with experts from the Whale Sanctuary Project created a responsible operational plan to bring Tokitae to her home waters in the Salish Sea should that be decided that’s the best future for her.

Things that had to be factored into that decision were her age and her health (not just hers but that of other whales in case she could pass on infections she’s picked up in captivity).

However, a very persuasive argument that supported her rehabilitation and release is that she had proven to be a strong and resilient whale to survive so long in captivity and that she would also display those characteristics if re-introduced into the wild.

In March 2023, the owners of the Miami Seaquarium announced a “formal and binding agreement” with the Friends of Toki group to begin the process of returning Tokitae to Puget Sound.

A detailed plan was yet to be released (a news release mentioned working toward and hope of a relocation being possible in the next 18 to 24 months) and federal agencies would have to sign off on any plans to transport Tokitae.

It felt like, finally, there was a step in the right direction for the imprisoned orca whale.

But sadly in August 2023, her condition deteriorated rapidly and she died, provoking an outpouring of grief and sadness amongst people around the world. Read more in this NBC news article.

Find out more about the Sacred Sea Conservancy and the Whale Sanctuary Project.

Deep dive...into Pilot whales

The pilot whale is found in regions all over the world and has two species: the long-finned pilot whale lives in temperate or colder waters whilst the short-finned pilot whale can be found in tropical and subtropical waters.

Like the orca whale, the pilot whale is a toothed whale belonging to the dolphin family (Delphinidae). It’s the second largest cetacean in this group, after the orca, and it also has the nickname of ‘blackfish’.

It’s thought that pilot whales got their name because pods were/are believed to be ‘piloted’ by a leader. They are sometimes called ‘pothead whales’, particularly by people in Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada. It’s no surprise that this nickname comes from the fact that they have a globular head, including a bulbous melon.

This mass of fatty tissue, located at the front of the head, focuses and modulates the cetacean’s vocalisations. It’s also key for its echolocation ability. The pilot whale’s head was thought by whalers to resemble black pots or cauldrons, hence the name ‘pothead whales’.

The species is black or dark grey in colour except for a light saddle behind the dorsal fin, and its white belly. It has a very slight beak and sharp teeth.

The long-finned and short-finned species of pilot whale look similar to each other while moving through the water as the difference in their fins isn’t obvious. The long-finned species is usually a larger weight than the short-finned one and their skulls are different too, so skull analysis is a good way to tell them apart.

Pilot whales are usually between 4-6 metres long, the males of both species being larger than the females. They usually travel in large matrilineal pods (often ranging from 20 to 100 whales in each pod), are highly intelligent and social, and may remain in their birth pod throughout their lifetime.

The average life span for males of both species is 45 years. Female long-finned pilot whales live to 50, on average, and their short-finned counterparts make it to an average of 63 years of age.

Pilot whales are known to be one of most docile whale species, which is explains why it’s a species that marine parks have sought to keep in captivity and on display.

Speedy species

Pilot whales are often called “the cheetahs of the deep sea”, on account of their high-speed dives to catch their prey. A study in the Canary Islands in 2008 showed that they make up to 15 minute long dives to a depth 1,000 metres to chase and catch squid, before swimming back to the surface to catch their breath.

The study’s lead author, Natacha Aguila de Soto, said, “They make colossal dives and must come back exhausted. They have to spend time at the surface catching their breath before undertaking a new sprint to catch prey.”

Pilot whales can reach a speed of up to 32 kilometres an hour while chasing prey.

Strandings

Pilot whales are prolific stranders and the reason why is not fully understood. Individual whales strand usually because they are ill or injured and mass strandings are harder to figure out.

One theory is that pilot whales’ echolocation skills are not suited to shallow, gentle sloping waters (they prefer deeper areas further out into the ocean) and that they may inadvertently beach themselves while following food sources inshore, particularly in the summer.

As they tend to travel in large pods, it may be that one whale loses its way and strands itself, others follow to aid it and end up getting stranded too.

The biggest recorded pilot whale stranding was an estimated 1,000 whales at New Zealand’s remote Chatham Islands back in 1918. The islands has been the location of many more strandings since, making it a hotspot for pilot whale strandings.

Where do they live?

Pilot whales can be found in both coastal and pelagic (open sea) areas.

The long-finned pilot whale lives in colder waters, such as the North Atlantic Ocean (e.g. off Greenland, Iceland), North Pacific Ocean and the Southern Ocean (also known as Antarctic Ocean). They are occasionally seen off the west and south west coasts of Ireland and are found in the Strait of Gibraltar.

They are regularly sighted in waters off southern Australia and New Zealand and are found off coastal South America.

While it doesn’t live in the tropics, it’s believed long-finned pilot whales transit through the tropics from time to time, connecting populations.

Short-finned pilot whale lives in warmer (tropical and sub-tropical) waters, in both hemispheres. They are the most commonly found cetacean in the Canary Islands, for instance, with an estimated population of 2,000.

Pilot whales are generally nomadic but there is a stable and resident short-finned population in the southwest of Tenerife, and there are also sizeable resident groups in California, Japan and Hawaii. They’re also found seasonally in areas including the Caribbean, Bahamas, parts of the African coast, Central and South America coasts, the Middle East, Asia and off the coast of European countries including Spain and Portugal.

Short-finned whales are also found in the southern Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Generally, the species occupies the outer edges of the continental shelf, though they can also be seen closer to the shore.

What do they eat?

The primary food of pilot whales is squid. Both species have about half the number of teeth compared to other dolphins, as a special adaptation for eating squid. They eat relatively large-bodied species of squid, along with octopus and cuttlefish, and fish such as herring, cod and turbot, on occasion.

Adult pilot whales can eat up 30kg of food per day and usually hunt in groups, deep diving down to much lower levels of the ocean to find squid.

Population

The global population for both species of pilot whale is unknown though estimates suggest that there could be in excess of 1 million whales in total (thought to be c.700,000 – 1 million long-finned pilot whales and c. 200,000 to 300,000 short-finned pilot whales).

Both species of pilot whale are listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List. However, they do face many threats and risks (see below) which gives weight and credence to protecting and conserving the species.

Threats to pilot whales

Hunting

Sadly, in some areas of the world, pilot whales are still hunted.

The Faroe Islands in Denmark has a whaling season every year during the summer months, which is referred to as the “grind”.

Primarily pilot whales are rounded up by boats and herded into a semi-circle in shallow waters. They’re forced to beach, where they are killed with a deep cut through the dorsal area, which severs the spinal cord.

Photos every year show horrific bloodied waters around the dead pilot whales and other dolphins. The hunters justify the action saying it is a traditional hunt that has taken place for centuries but animal welfare groups have long campaigned that it is archaic, cruel and unnecessary. Usually around 800 pilot whales are killed this way every year – for more check out this informative Newsweek article from June 2022.

Long-finned pilot whales are also hunted in Greenland, on an opportunistic basis, mostly in the southwest of the island and hunted from small boats using rifles and hand harpoons.

Short-finned pilot whales are also hunted in drive fisheries in some regions around the world, including Japan. The species is amongst the many dolphin species that are herded into Taji (well-known through the documentary The Cove) and slaughtered for meat.

The species is also permitted to be hunted in St Vincent and the Grenadines (check out this Frontiers in Marine Science paper from 2021 for more info).

Ship strikes

Vessel strikes present a risk to pilot whales, especially in areas where their movement overlaps with busy shipping lanes and/or or leisure boat and ferry activity.

Entanglement/fishing bycatch

Like other species of whales and dolphins, pilot whales can become entangled in fishing gear and either swim off with the gear attached or become anchored (both of which can lead to fatigue, compromised feeding ability and ultimately cause death).

Pilot whales are also at risk of becoming bycatch in fisheries.

Reduced food sources

Fishing pressure, especially due to commercial fishing, can reduce the food source available to all whales, including pilot whales.

Noise, pollution and environmental change

As with other whale species, increasing underwater noise from vessels can negatively affect pilot whales, changing their normal behaviour and prompting them to move away from important breeding or feeding areas.

Climate change is leading to increased ocean acidification, which has a detrimental knock on effect on the animals living in our oceans. Pollution is also a great threat to the health of our marine mammals.

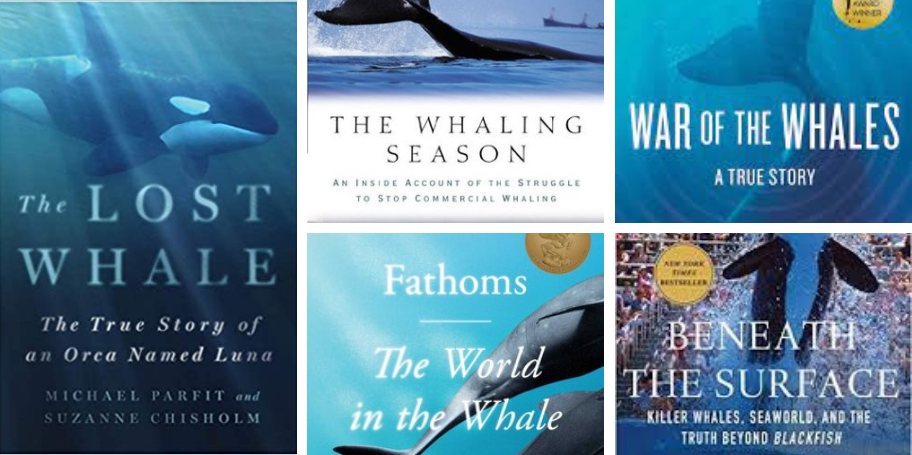

Passionate about whale protection? Five books you need to read…

If you want to learn more about whales and the issues they face around the world, there’s no better way to get up to speed than reading a good book. We’ve gathered five of our favourite titles, each covering different areas of whale awareness and protection. Read on to get the lowdown.

Lost Whale: The True Story of an Orca Named Luna

Written by Michael Parfit and Suzanne Chisholm. Published by St Martin’s Publishing Group.

This engrossing book followed on from the release of the documentary The Whale in 2011, which was narrated and executive produced by actor Ryan Reynolds. The film’s directors, Michael Parfit and Suzanne Chisholm, take on writing duties for the book which captures the story of an orca whale Luna who becomes separated from his pod at a young age.

Orcas are highly social animals and lonely Luna soon seeks out human contact off Vancouver Island in Canada. People are warned not get too friendly with the young orca as it may ultimately cause harm to him if he gets too used to human interaction. It’s hard, though, to turn your back on a creature seeking out contact, wanting to have his tongue rubbed and squeaking and whistling in a fun game with people. Several groups try to come up with a solution to Luna’s isolation, including a proposal to reunite him with his pod. But will it go to plan?

War of the Whales: A True Story

Written by Joshua Horowitz. Published by Simon & Schuster.

Reading like a thriller novel at times, this book is factual. It follows attorney Joel Reynolds as he uncovers a submarine surveillance system run by the U.S. Navy, which floods ocean basins with high-intensity sound.

Joel teams up with marine biologist Ken Balcomb to expose the truth behind this system and the connection to mass strandings of whales. This leads to a high stakes courtroom battle. Expect lots of twists and turns in the story.

Beneath the Surface: Killer Whales, SeaWorld and the Truth Beyond Blackfish

Written by John Hargrove. Published by Palgrave Macmillan.

It’s almost 10 years since documentary film Blackfish was released in 2013. It’s had a huge ripple effect in a relatively short period of time. John Hargrove was one of seven former SeaWorld trainers who was critical of the company in the documentary.

He penned his own book in 2015. It tells a compelling story of a boy with a childhood dream to become an orca trainer and the road he went on to make that happen. Over 14 years, John worked with 20 different whales on two continents and at two of SeaWorld’s U.S. facilities. He increasingly began to realise that keeping orcas in captivity was harmful to the animals and risky for the trainers who work with them (he documents his own multiple physical injuries from working with whales in the water).

John also tells the stories of whales he came to know and love during his time as an orca trainer. The difficult decision he made to leave SeaWorld in 2012, knowing he would no longer see them or care for them, comes across as a very moving part of the book. John has continued with his advocacy to shut down marine parks and encourage tourists not to visit them. Take a look at a recent blog he wrote on the subject for Peta.org.

The Whaling Season: An Inside Account of the Struggle to Stop Commercial Whaling

Written by Kieran Mulvaney. Published by Shearwater Books.

The author of this book, Kieran Mulvaney, is co-founder of the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (now known as Whale and Dolphin Conservation). He was also a campaigner and coordinator for four Greenpeace expeditions to Antarctica to intercept whaling ships and use nonviolent means to stop their slaughter of whales.

He recounts those voyages in the 2003 book The Whaling Season, combining personal narrative and behind-the-scenes info with a bigger story about the development of Greenpeace, the history of commercial whaling and scientific information on whales. The book also examines the forces at work in international whale politics. Highly readable and both informative and stirring in its plea to protect our ocean’s whales.

You might also like to read Kieran’s Washington Post Magazine cover story The Loneliest Whale in the World?

Fathoms: The World in the Whale

Written by Rebecca Giggs. Published by Simon & Schuster.

This 2020 book opens with writer Rebecca Giggs encountering a humpback whale that had stranded and died on a beach in her native Australia.

It’s the beginning of a journey in which she explores what whales mean to us, how they have managed to survive despite the harm brought by humans, and the threats they continue to face due to our environmental crisis (acidification of oceans and pollutants to name but a couple) along with net entanglement, ship strikes and noise pollution.

It’s a book full of insight as Rebecca travels around the world to see and learn more about our varied whale species. And it’s a joy to read with its lyrical sense of writing.

Deep dive…into Blue whales

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) rules the ocean. It’s the largest animal ever to have lived on earth (yes, larger than any dinosaur).

The species can grow up to 30 metres long and weigh in at a whopping 180 tonnes. A blue whale’s tongue alone weighs as much as an elephant and its heart as much as a small car.

It belongs to the baleen whale group and can be recognised as such by the plates of baleen (rather than teeth) suspended from the upper jaw, and the two blowholes on the upper body. Its dorsal fin is very small and is set far back on the body.

The blue whale has a long, slender body and it gets its name from its blue colouration. However, it only looks true blue underwater. When it surfaces, the colour is more of a mixed grey-blue. Its underbelly has a yellowish hue from the millions of microorganisms that take up residence on its skin. The blue whale is sometimes called the sulphur bottom whale because of this yellow tinge to its skin.

On average, blue whales live around 80-90 years. The oldest blue whale recorded was estimated (using ear plug analysis) to be 110 years old. Blue whales swim at an average of 8 kilometres an hour but can accelerate to more than 32 kilometres an hour when they’re agitated.

Blue whales are the loudest animals on earth, reaching around 188 decibels. That’s far more than a jet engine’s sound (140 decibels). Scientists believe that in good conditions, blue whales can hear each other up to 1,600 kilometres away. They vocalise to communicate with other blue whales and along with their awesome hearing, to sonar-navigate the ocean depths.

Where do they live?

Blue whales prefer living in deep temperate cold waters. There are two reasons why – they have a significant layer of blubber which helps to keep them insulated and the majority of their food also likes to live in cold waters.

Blue whales can be found in all of the world’s oceans. They’re generally more common in the Southern Hemisphere (Antarctica, Australian and New Zealand waters). There’s also a resident population in the northern Indian Ocean.

In the North Atlantic Arctic, the blue whale can be spotted around Norway, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, in southern Greenland, and in southern Svalbard. They’ve also been occasionally spotted in North Atlantic waters west of Ireland and Scotland. In 2021, there was great excitement when a blue whale was spotted just off the coast of Co Galway, the first time in six years that the species had been sighted in Irish waters. You can read more about the sighting in this Irish Post article.

2021 also saw an unusual blue whale sighting on Spain’s Atlantic Coast, following on from previous identifications in 2017, 2018 and 2020. Blue whales were spotted off Galicia, where they hadn’t been seen in 40 years. The species was almost extinct in that region as a result of historic whale hunting. You can read more about the Spanish sighting in this Guardian article.

Generally speaking, blue whales spend their summers feeding in cold waters and then migrate long distances to warmer waters (nearer the equator) for mating season.

The Eastern North Pacific population of blue whales mostly feed off California from summer to autumn and then move north to colder waters off Oregon, Alaska and Washington State to continue feeding. During winter and spring, they migrate south to the waters of Mexico (mostly the Gulf of California) and the Costa Rica Thermal Dome.

Blue whales are occasionally seen swimming in small groups but are more often found migrating alone or in pairs (particularly with offspring). The gestation period for a blue whale is 10-12 months and offspring are always born in warmer waters.

What do they eat?

Like other baleen whales, blue whales have expandable pleats (or baleen) which allow them to take in huge amounts of water and food. They can often be seen rapidly performing twists and turns with their entire body to locate tiny shrimplike animals (krill) and grab as much of it as possible.

They sieve the water out through their pleats and then ingest the krill remaining in their mouths. It had been thought that blue whales eat around four to eight tonnes a day but new research suggests they could be eating around three times as much a year as previously estimated. The study in Nature magazine shows evidence that a blue whale in the eastern North Pacific might eat between 10 and 20 tonnes of food a day!

Population

The blue whale was driven to almost extinction by commercial whaling in the 1900s. A single blue whale, being the size that it is, yielded a lot of whale oil so it sadly comes as no surprise that whale hunters were keen to track them down and slaughter them.

It’s estimated that between 1900 and the mid 1960s, some 360,000 blue whales were killed.

The species has been protected from hunting by the International Whaling Commission since 1966 and there is some evidence to suggest that populations are recovering. It’s difficult to assess blue whale numbers because many populations appear to still be small and because the species is widely distributed in offshore waters.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the pre-hunting population size was estimated to have been as many as 200,000–300,000 whales. After intensive hunting in the Antarctic region took its toll, the numbers dropped dramatically. Blue whales were estimated to number around 2,300 in 1998 and to be increasing between 2.4 – 8.4% each year.

Globally, the species is listed as Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List with the Antarctic subspecies listed as Critically Endangered.

Threats to blue whales

Ship strikes

Vessel strikes present a risk to blue whales, especially in areas where their movement overlaps with busy shipping lanes e.g. off the coast of California and Sri Lanka. Larger vessels and ships travelling at high speeds particularly pose a threat of injury or death to whales.

Entanglement

Blue whales can become entangled in fishing gear and either swim off with the gear attached or become anchored. If they swim off with gear attached, it can ultimately cause fatigue and compromised feeding ability.

Accidental entanglement poses a greater threat to other whales and dolphins though than it does to blue whales. Their bigger size and strength helps them to break freely more easily than other species. Death from entanglement is more rare in blue whales though it’s not unheard of.

Noise, pollution and environmental change

As with other whale species, increasing underwater noise from vessels can negatively affect blue whales, changing their normal behaviour and prompting them to move away from important breeding or feeding areas.

Climate change is affecting our ocean and the creatures that live within it. Commercial exploitation of krill and climate change affecting the distribution of kill in our ocean both negatively impact blue whales. More research is needed, though, to quantify exactly what the effects have been.

Natural predator

The only known natural predator of blue whales is the orca but due to the blue whale’s massive size and its ability to outswim other whales, it’s usually calves who are targeted for predation. Interestingly though, in January 2022, a report was published with scientists documenting the first known case of a pod of orcas killing an adult blue whale.

The Wonderful World of Whales

The lives of whales are truly fascinating. Here are five facts you probably didn't know!

Whales sleep with one half of their brain awake

Humans find it very easy to have prolonged periods of unconscious sleep. When we drift off at night, we’re not aware of our surroundings for long periods of time.

However, whales sleep in a very different way because their breathing is not automatic. They have to actively and consciously decide when to breathe, in order to stay alive.

To do this, whales only allow one half of their brains to sleep at a time. The other half stays alert so they that continue to breathe (and also are conscious of potential dangers in their surroundings). This is called unihemispheric slow-wave sleep.

Scientists have found that whales (and dolphins) only close one eye when they sleep and they alternate which half of the brain sleeps at a time. When sleeping, whales will often rest motionless at the surface, breathing regularly, or they may swim very slowly and steadily just under the water’s surface.

A team of scientists observed sperm whales ‘drift diving’ close to the surface water in 2008. In other words, they were taking a nap together as a group. The researchers onboard found that the sperm whales spent just 7% of their day napping, for bursts of around 10 to 15 minutes each time.

You can tell how old a whale is from its earwax

Accessing info to figure out the age of a whale or dolphin has been difficult in the past for researchers. But there is one surprising way that we can learn about whales – their earwax!

A dense wax plug builds up in a whale’s ear canal (this is particularly the case for some species of baleen whales and in sperm whales) and grows consistently throughout its lifetime. Think of it a bit like tree rings that keep adding over the years.

These ear plugs allow researchers to age a whale and also to see what sort of pollutants and stresses they were exposed to throughout their lives.

When it comes to how old a whale is, the trick is to look out for alternating light and dark layers within the ear plug material. Light layers are associated with periods of feeding and dark ones are connected with periods of migration or when the whale wasn’t feeding.

Usually, a year in the life of a whale will be made up of one light and one dark layer so that’s how researchers can figure out how many years the whales were alive.

Earplugs are gathered from whales that have died from ship strikes, strandings or entanglement in fishing gear.

The technology with earplug analysis has advanced greatly in recent years though it still involves painstaking work. A new technique from Baylor University was used on a single earplug obtained from a male blue whale that died from a ship strike. Researchers could quantify lifetime levels of two hormones and 42 contaminants from this one earplug – some very valuable information.

You can find out more about what was discovered about this blue whale’s life in this 2013 Smithsonian Magazine article.

The team at Baylor University have gone on to discover lots more from ear plug data from whales. A 2018 paper looked at stress hormone levels in ear wax, showing how hunting and climate change have impacted whales. The team used samples from three types of baleen whales, from both Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

We’re still figuring out why some whales breach

Breaching is when a whale leaps out of the water, bringing almost all of its entire body up in the air for a large jump. It’s an amazing sight to behold – not one you would easily forget!

But exactly why whales breach is still not clear to us. There are a few different possibilities – including courting other whales, shaking parasites off their skin or simply to make a sound by splashing back in the water (they may be communicating to other whales, including signalling a warning).

Baby whales that have lost their mothers have been observed breaching repeatedly – probably to send both a visual and audio signal to its mother.

The other strong possibility is that the whale is playing. There may not be any other reason apart from the explanation that jumping out of the water and splashing back down is fun!

Whales can live for more than 200 years

Many species of whales live for between 70 and 100 years. But we know that some whales live a lot longer.

The oldest known whale is a bowhead whale – at a whopping 211 years old. The whale had been hunted for food by native people in the Arctic and subsequent testing using amino acids from the eye concluded its age was well over the two century mark.

Previously, three bowhead whales killed in northern Alaska were estimated to be between 135 and 172 years old. In this same area of Alaska, hunters have reported finding ivory and stone harpoon points (from previous attacks) in the blubber of freshly killed bowhead whales. These implements hadn’t been used since the 1880s.

Orca sometimes beach themselves to hunt

When a whale beaches itself, it’s usually because it is ill, disorientated, injured or dying. It’s not something a healthy whale usually does as it’s a risky move if it gets stuck and can’t get back to the safety of water.

But the orca whale is willing to take the risk on occasion. In the Peninsula Valdés in Argentina, a small group of orca hurl themselves out of the ocean to catch and kill beach-dwelling sea lion pups. The activity needs to be very carefully timed with a wave coming into the beach and it’s all about getting in the right position at the right speed.

It’s a surprise move, to take the sea lions unaware. The orca aims to successfully catch its prey and then catch the next wave off the beach. A steep and pebbled beach helps them to roll back to the water.

Tourists can spot this occurring from a look out point at Punta Norte on the Peninsula Valdés though it’s important to point out that there’s a very short window to spot it each year.

The peak season for orcas to hunt this way is 10 to 15 days, usually in March or April. This is when baby sea lions are learning to swim. The attack time is only two hours before until two hours after high tide.

This feeding behaviour was first documented in 1976 and scientists believe it to be a learned behaviour rather than instinctive.

Check out this great video from Associated Press showing the orcas in action.

Deep dive...into Fin whales

The fin whale is the second largest animal on earth, after the blue whale. It gets its name from a distinctive fin about two thirds of the way on its back. Fin whales have streamlined, sleek bodies with a pointed head (rostrum).

They belong to the baleen whale family group and specifically the rorqual sub-type, which also includes blue whales, humpback whales, sei whales and minke whales.

Fin whales have very unique colouring – they are dark grey on the back and light on the underside. Both the belly and the underside of the flippers are almost white. Even the colouring on its head is highly asymmetric – its left side is dark grey and the lower parts of the right side are bright white.

Many fin whales have ‘chevrons’ which are light grey in colour and start just behind the blowhole, continuing along the back of the body in the shape of broad V’s.

And speaking of blowholes – the fin whale produces a tall columnar blow that can be up to six metres high. A telltale sign to spot them in the water.

The species is called the ‘greyhound of the sea’ for good reason. Fin whales can cruise at up to 15 kilometres per hour and can accelerate in short bursts of speed of up to 28 kilometres per hour.

Their lifespan is 80-100 years old and average weight is 40-80 tonnes.

On the shy side

Fin whales are generally solitary or found in pairs. They’re rarely be found in large groups. The species tends to stay out of the limelight. They rarely breach or spyhop and they avoid raising their fluke out of the water for much of the time.

In the early days of whaling, the fin whale’s speed in the water made it a difficult target for hunters. But as boats got faster and hunting tools evolved, that advantage disappeared.

The species was relentlessly hunted for its oil, meat and baleen with hundred of thousands of animals believed to have been slaughtered. Sadly, the fin whale is still hunted in some parts of the world today.

The global population is estimated to be between 50,000 and 90,000. It’s difficult to put a firm figure on it as they spend so much time out in ocean waters and are less likely to be spotted. The fin whale is listed as an endangered or vulnerable species in several regions.

Where do they live?

Fin whales are usually found out in the open ocean as opposed to coastal waters. Like other large whales, fin whales’ behaviour sees them migrating between feeding and breeding grounds. Their seasonal movements are less predictable and understood than other baleen whales. There’s still a lot to be learnt about how this species lives.

You can find resident fin whale populations in some part of the world, including the Gulf of California in Mexico, the East China Sea (off Japan) and the Mediterranean Sea.

Fin whales prefer cooler waters so you won’t find them popping up in tropical waters any time soon! The largest population is thought to be in the North East Atlantic with an estimated 25,000 – 30,000 fin whales living there.

Cooler offshore waters where they are spotted around the world include the waters around Argentina, Ireland, Canada, Norway, Spain, Greenland, Iceland, Brazil, Denmark, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, the U.S., Morocco and many more.

What do they eat?

Like other baleen whales, fin whales have expandable pleats which allow them to take in huge amounts of water and food.

They spend several hours each day feeding and are lunge feeders, which means they roll on their sides with gaping mouths open to take in the food.

Then they sieve the water out through their baleen plates before they ingest their tasty catch. Fin whales consume up to two tonnes of krill in a day, along with small fish and crustaceans.

Threats to fin whales

Ship strikes

Whale hunting was once the biggest threat to fin whales but the most pervasive threat now is ship strikes. This is especially true in the Mediterranean Sea. An annual study of seasonal feeding aggregation of fin whales off the Catalan coast (Spain) has taken place since 2014.

Its finding is that ship strikes represent the greatest conservation threat for fin whales in the Mediterranean Sea with at least four fin whales found dead in Barcelona Port since 1986 due to ship strikes. Seven live whales have been documented with injuries in the study area since 2018.

Noise

Fin whales are one of the loudest animals in the ocean with a frequency sound of up to 196.9dB. When there is competing underwater noise from vessels, it can negatively affect fin whale populations who will change their normal behaviour and move away from important breeding or feeding areas.

It is also possible that prolonged exposure to noise can increase the chances of a fin whale becoming disorientated and/or stranding.

Environmental change

This can lead to both loss of habitat (as waters become warmer) and lack of food for fin whales. Plastics and micro plastics in the ocean pose a threat to whales, along with all other marine mammals and fish. As do chemical pollutants entering into the water ecosystem.

Changing water temperature and currents can impact the timing of important environmental cues for whales such as when it is time to depart to feed or to migrate to breed.

Entanglement

Like other whales, fin whales can become entangled in fishing gear. They can either become anchored and die or swim off with the gear (which usually results in fatigue, compromised feeding ability or severe injury and ultimately can lead to death).

Natural predators

The only known natural predator of fin whales is the orca but due to the fin whale’s large adult size, it’s usually calves who are targeted for predation.