Conservation Programmes launched on WeWhale website

WeWhale is excited to launch a new conservation programmes section on our website, showcasing three different programmes that passionate whale and dolphin lovers can take part in.

The Lanzarote Conservation Programme has been running since summer 2023 and is now joined by a new Tenerife programme and Iberian Orca programme.

Participants in the Canary Island programmes have the opportunity to be part of a unique movement and mission to make whale observation trips noise and emission free. They are enriching programmes - participants get to experience whales and dolphins in their natural habitat, learn about species and their behaviours, help to create awareness about the challenges they face, compile and build databases about whale and dolphin sightings, and get hands-on experience working with the WeWhale team.

There are plenty more highlights and aspects to the programmes, which can be found on each of the conservation pages.

The Iberian Orca Conservation Programme has been developed in tandem with WeWhale Association’s Save the Iberian Orca project.

The project, running between April and October, sets out to prevent attacks from boaters on the critically endangered Iberian Orca, survey the population, and track and analyse interactions among boats and orca. There is both a sea-based and land-based element to this programme, which participants will be fully involved in.

There are less than 35 Iberian Orcas left in the Strait of Gibraltar, where they are under increased pressure from maritime traffic, pollution and aggressive interactions from recreational boaters. The motivated and determined volunteers on our Iberian Orca Conservation Programme make a real difference in safeguarding this important whale species. Further information about the “Save the Iberian Orca” campaign can also be found at www.save-the-iberian-orca.org

Details on all of WeWhale’s Conservation Programmes, and how to apply, are on our website right now!

WeWhale launches ‘Save the Iberian Orca’ GoFundMe Campaign

A new campaign to help protect the critically endangered Iberian Orca has been launched by WeWhale Association (part of the WeWhale group).

The small subpopulation (estimated to be ca.35 individuals), that lives in the Strait of Gibraltar from the beginning of April to the end of October, faces numerous threats including maritime traffic, pollution, and, increasingly, aggressive interactions from recreational boaters.

WeWhale this week launched a GoFundMe campaign whereby animal lovers can donate money to help fund a comprehensive surveillance and protection programme, both at sea and on land.

A sea-based team is planning to be on patrol five days a week, surveying the orca population, preventing attacks on the orca from boaters, and helping to avoid possible interactions between boats and orca. This work is being supported by Sea Shepherd France.

At the same time, a land-based crew will observe and monitor the orca population from strategic coastal locations.

Donations to the GoFundMe will directly fund equipment and resources for the surveillance teams, research and analysis to better understand orca behaviour and interactions, and advocacy efforts to raise awareness and enforce protections for the Iberian Orca.

WeWhale is proud to launch the GoFundMe campaign with a special video, in partnership with zoologist and wildlife presenter Billy Heaney.

Billy features in the video, speaking about the reported interactions between Iberian Orca and boaters, particularly over the last three years, the reasons why these interactions are happening, and why these animals need to be protected via this campaign.

Founder of WeWhale, Janek Andre said, “We are delighted to be launching this GoFundMe campaign, with a view to beginning the surveillance and protection programme this April. With only 35 individuals left, the situation is dire for Iberian orca.

“More than 500 interactions between Iberian Orca and boats have been reported from 2020 to 2023, escalating to the point where recreational boaters have begun to use violence, shooting at approaching orca.

“Continued interactions pose a significant threat to the survival of this important subpopulation and the years 2024, 2025 and 2026 are pivotal in ensuring their survival. We cannot stand by and do nothing while this population is increasingly under threat. The time to act is now. With your support, we can protect and preserve the Iberian Orca for generations to come.”

In August 2023, a recreational boat crew was observed and filmed shooting at orca, as they were approaching the vessel in the Strait of Gibraltar.

WeWhale, along with the World Cetacean Alliance and Sea Shepherd France, filed charges against the captain and boat owner. This case is currently making its way through the Spanish court system.

You can view the launch video here:

And contribute to the Save the Iberian Orca GoFundMe page.

For donations over €50, an Iberian Orca postcard will be sent to donors. The Iberian Orca apparel collection can be be bought under https://wewhale.co/shop and 100% of the profits of the collection will be dedicated to fund our campaign. All of these beautiful items are designed by ocean artist Rachel Brooks.

Deep dive...into Cuvier's beaked whales

The Cuvier’s beaked whale is one of the larger members of the beaked whale family. Found in most oceans and seas around the world, the species has the most extensive geographical range of all the beaked whales.

It has a long robust body with a dark grey back and sides, and much paler belly and head. It also has panda-like dark eyes around each eye. In some locations, the Cuvier’s beaked whale appears to have a brownish body because it’s covered in algae.

The profile of its head is conical and is sometimes described as ‘goose-like’, which lends them the name ‘goose-beaked whales’. The jaw-line is slightly upturned which gives them a ‘smiling’ appearance.

Like other beaked whale species, males have a pair of small cone-shaped teeth (resembling tusks) that come out of the tip of their bottom jaw, and are often used for fighting.

Scars on their bodies come from scrapes they get into during their active lifestyles and also bites from other animals (such as cookiecutter sharks) or from competing males of the same species. Their scarring patterns help researchers to identify individuals.

Cuvier’s beaked whales have a slightly bulbous melon, an indistinct beak and a small curved dorsal fin located far down their backs. They weigh between 1,800 and 3,000 kilograms and reach lengths of between five to seven metres.

As they get older, the whales become paler and develop more significant indentation at the top of the head.

It’s often hard to distinguish between the many species of beaked whales and they are also challenging to observe when at sea due to them keeping a low profile, spending only limited times at the water’s surface and their small, inconspicuous blow. Beaked whales are sometimes confused with the northern bottlenose whale.

When at the surface, the species doesn’t often breach but when it does, it’s been observed as being torpedo-like.

Cuvier’s beaked whales are the deepest and longest-diving marine mammals in the world. The deepest known dive for this species was 2.9 kilometres and the longest known dive lasted a whopping 3 hours 42 minutes! This was recorded in 2020 – see this Science News article for more.

They dive deep so they can feed on cephalopods (squid and octopus) that live in the further reaches of the ocean.

Cuvier’s beaked whales are usually found on their own or in small groups of around two to seven individuals. Though they prefer small groups, they are quite sociable animals. Global records show that Cuvier’s beaked whales are the most frequently stranded species amongst the beaked whales.

The whale gets its name from Georges Cuvier, who first described the species in 1823 from a skull found on a beach in southern France.

Where do Cuvier’s beaked whales live?

The species is found in temperate, subtropical and tropical waters. Cuvier’s beaked whales prefer deep pelagic waters and are found in most oceans and seas worldwide (except for the polar seas).

A lot of the information we have on their locations is from stranding records as opposed to sightings, as they are usually far out in the ocean and remain underwater for long periods. Little is known of their migration patterns.

They are usually found in areas including the Bay of Biscay, British Columbia, the Gulf of California, Mediterranean Sea, the Shetlands, the Gulf of Mexico, Massachusetts coastline, New Zealand, South Africa and Tierra del Fuego in South America. There have also been recorded strandings in the Bahamas, Caribbean Sea and the Galapagos Islands.

Population

On the IUCN Conservation Red List of Threatened Species, the Cuvier’s beaked whale is listed as least concern. No global population figures exist but they are one of the most abundant of the beaked whale species.

What do they eat?

Cuvier’s beaked whales are big fans of squid and eat at least 47 types of it! They also eat fish and crustaceans.

Since they don’t have teeth (apart from the two small tusks that males have), they use a suction method in their mouth using their ventral throat grooves. This allows them to slurp and suck in squid and other food.

Threats to Cuvier’s beaked whales

Ocean noise

As they are deep diving whales, one of the biggest threats to Cuvier’s beaked whales is noise emitted from a ship’s sonar. This confuses their echolocation which they use to find food, to navigate and to communicate.

The species can panic and surface too quickly if frightened by noise. In which case, they suffer decompression sickness, or ‘the bends’, just like human divers too.

It’s thought that mass strandings of the species could be linked with military activity underwater – this has been reported particularly in the Bahamas, Caribbean Sea and Mediterranean Sea. There were instances in the Canary Islands but since naval exercises using sonar were banned there, no further mass strandings have taken place.

Entanglement in fishing gear

Like other cetaceans, Cuvier’s beaked whales can become entangled in fishing gear which goes on to cause injury, fatigue, comprised feeding, and sometimes even death.

Vessel strikes

Cuvier’s beaked whales are at risk of vessel strikes throughout their range but the threat is much higher in areas with busy ship traffic.

Environmental change and pollution

Climate change and pollution are a threat to all whales and dolphins because of the loss of habitat as waters become warmer.

Plastics and micro plastics, along with chemical pollutants, entering into the water system are a serious threat to all creatures in our ocean.

As Cuvier’s beaked whales are suction feeders, they sometimes mistake plastic bags and other plastic materials for prey and ingest them. They can settle in their stomach, causing them to starve and die.

Hunting

The species has been taken in Japanese whaling operations, usually opportunistically as part of a hunt for the larger Baird’s beaked whale.

The WeWhale Pod Episode 13 - Naomi Rose

Our guest for this episode of The WeWhale Pod is Naomi Rose, senior scientist (marine mammal biology) for the Animal Welfare Institute in Washington D.C. and marine mammal protection advocate.

Naomi talks about her path into studying marine mammals and her particular love of orcas.

As a co-author of The Case Against Marine Mammals in Captivity report, Naomi explains that the body of science has grown over the years about whales and dolphins, along with other marine mammals, that are kept in captivity.

She chats also about the 'Blackfish Effect', which happened following the release of the groundbreaking documentary and her memories of visiting Tokitae, the orca who was kept for 53 years at Miami Seaquarium.

Take a listen to the episode below:

Thanks to Skalaa Music for post-production.

You can listen to previous episodes on our Podcast Page.

Deep dive…into Bottlenose dolphins

The bottlenose dolphin is one of the most well-studied marine mammals in the wild. Found in both inshore and offshore waters, it weighs approximately 200 kilograms and measures up to four metres long.

There are two species of bottlenose dolphins – the common bottlenose (Tursiops truncatus) and the Indo-Pacific bottlenose (Tursiops aduncus).

The common bottlenose species is instantly recognisable by its uniform grey colour (with a paler underside), its dorsal fin, and its stubby snout and elongated jaw (which often resembles a smile).

The bottlenose is also a larger species compared to other dolphins, although the Indo-Pacific type is slightly smaller than its common bottlenose cousin. The Indo-Pacific also has spots on its belly and has more teeth.

The cetacean is often known for its active and acrobatic style. It often breaches the water and bow rides with boats, regularly reaching speeds of up to 20 kilometres an hour.

Highly intelligent, the bottlenose dolphin travels alone or in groups (often the groups break apart and later reform). Bottlenoses have complex social structures and are generally quite curious, often approaching people to investigate what’s going on. When resting in groups, the species forms tight groups.

Bottlenose dolphins living closer to the coasts tend to be more territorial (squirmishes with harbour porpoises have been known to happen), while oceanic populations are more migratory in nature.

The dolphins use sound and echolocation, both to communicate and to hunt for food. Many of us would be aware of the interesting system of squeaks and whistles that they use.

Recent research by the University of Rostock in Germany has revealed a fascinating new discovery about bottlenose dolphins. Already well-known for their intelligence and activeness, they’re now suspected to have an additional sensory ability – being able to detect weak electric fields. Find out more about in this Earth.com article.

They have relatively long lifespans, with an average life expectancy of 40 years. Females have been observed outliving their male counterparts, reaching 60 years of age or more. Some individuals are known to be reproductively active for their whole lives, which is unusual among mammals.

The common bottlenose dolphin is listed as ‘least concern’ status on the IUCN Red List while the Indo-Pacific species is listed as ‘near threatened’ status.

Where do bottlenose dolphins live?

The common bottlenose dolphin is found in both inshore and offshore waters, typically found in temperate and tropical regions throughout the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans.

The Indo-Pacific bottlenose prefers warmer waters and is usually spotted in the Indian Ocean and western Pacific Ocean. They prefer shallow coastal waters and can often be seen in or around estuaries (one particular group, for instance, has made their home in the busy Port River in Adelaide, Australia).

What do they eat?

Bottlenose dolphins are quite adaptable, adjusting their food source depending on their environment. Most often, they will eat salmon, blue whiting, pollock, squid and crustaceans (shrimp and crabs).

They often work together to herd fish into groups, and then take turns swimming through the school of fish to feed themselves. They also use high frequency echolocation to locate their prey.

When they’re eating, they grip the fish with their teeth and then swallow it whole so the spines of the fish don’t catch in their throats. Bottlenose dolphins eat up to seven kilograms of food a day.

Threats to bottlenose dolphins

Entanglement in fishing gear

Getting caught up in fishing gear is a major threat to bottlenose dolphins around the world. It can cause injury, fatigue, comprised feeding and sometimes even death.

Dolphins particularly get caught up in commercial fishing nets for tuna.

Vessel strikes

Bottlenose dolphins are at risk of vessel strikes throughout their range but the threat is much higher in areas with busy ship traffic.

Environmental change and pollution

Climate change and pollution are a threat to all dolphins and whales because of the loss of habitat as waters become warmer.

Plastics and microplastics, along with chemical pollutants, entering into the water system are a serious threat to all creatures in our ocean.

Research shows that bottlenose dolphins in areas affected by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill were found to have compromised immune systems and decreased reproductive ability. Bottlenose dolphins living near the shore are more susceptible to habitat destruction and pollution caused by contaminants and oil spills.

Bottlenose dolphins can also be affected by harmful algal blooms, when they absorb toxins through the air or by eating contaminated prey. It can cause health issues or even death.

Bottlenose dolphins, like other cetaceans, use noise to communicate and to locate prey. Increased noise pollution from vessels and other human activity interferes with this ability.

Hunting/Predators

Bottlenose dolphins were once widely hunted for meat and oil, but that has fallen away over the years. Sadly, though, some limited dolphin hunting still occurs around the world.

As with other dolphin species, bottlenose dolphins are occasionally the prey of orcas and large sharks.

Deep Dive…into Whale and Dolphin Sanctuaries

Providing protection for whales and dolphins and acting as havens for formerly captive cetaceans, sanctuaries around the world play a vital role. We take a closer look at four whale and dolphin sanctuaries, some of which already exist and some which are currently in development (we’re counting the days till they become a reality!)

Umah Lumba Dolphin Rehabilitation, Release and Retirement Centre

The world’s first permanent dolphin rehabilitation, release and retirement facility for former performing dolphins, the Umah Lumba Centre is located in West Bali in Indonesia.

Umah Lumba means “dolphin house” in Balinese. The idea for the facility was initiated in 2019 by BKSDA Bali Forestry Department and the Ministry of Forestry, working with local partners Jakarta Animal Aid Network to supply human power and Dolphin Project to provide financial support and supervision.

The Centre stabilises recently confiscated dolphins from captive facilities and also aids stranded or injured dolphins. Once they are returned to good health, an assessment is made whether they’re good candidates for readaptation and release into the wild (in which case, they’re taken to Camp Lumba Lumba Readaptation and Release Centre).

If they’re not suitable candidates for release, dolphins are provided with a wonderful retirement home at the Umah Lumba Centre. They live out their lives in peace and comfort in a secure sea pen.

Two of the success stories at the Centre are Rambo and Rocky, who were amongst the group of dolphins rescued from the Melka Excelsior Hotel in Bali (where they performed for many years in small concrete pools). They regained their health and strength at Umah Lumba and re-learned how to catch live prey through live fish feedings.

In 2022, the dolphins, along with another dolphin Johnny, were given the choice of returning to the open ocean when the gates of the Centre were opened for them.

Unsurprisingly, they took the chance to swim free! The Centre continues to monitor the dolphins to check on their wellbeing.

As well as focusing on dolphin rehab and re-release, the Umah Lumba Centre provides medical aid and rehabilitation for turtles, including many endangered species.

Find out more: The Dolphin Project – Bali Sanctuary

You can also listen to The WeWhale Podcast Episode 4 with Femke den Haas, who is involved with the Umah Lumba Centre.

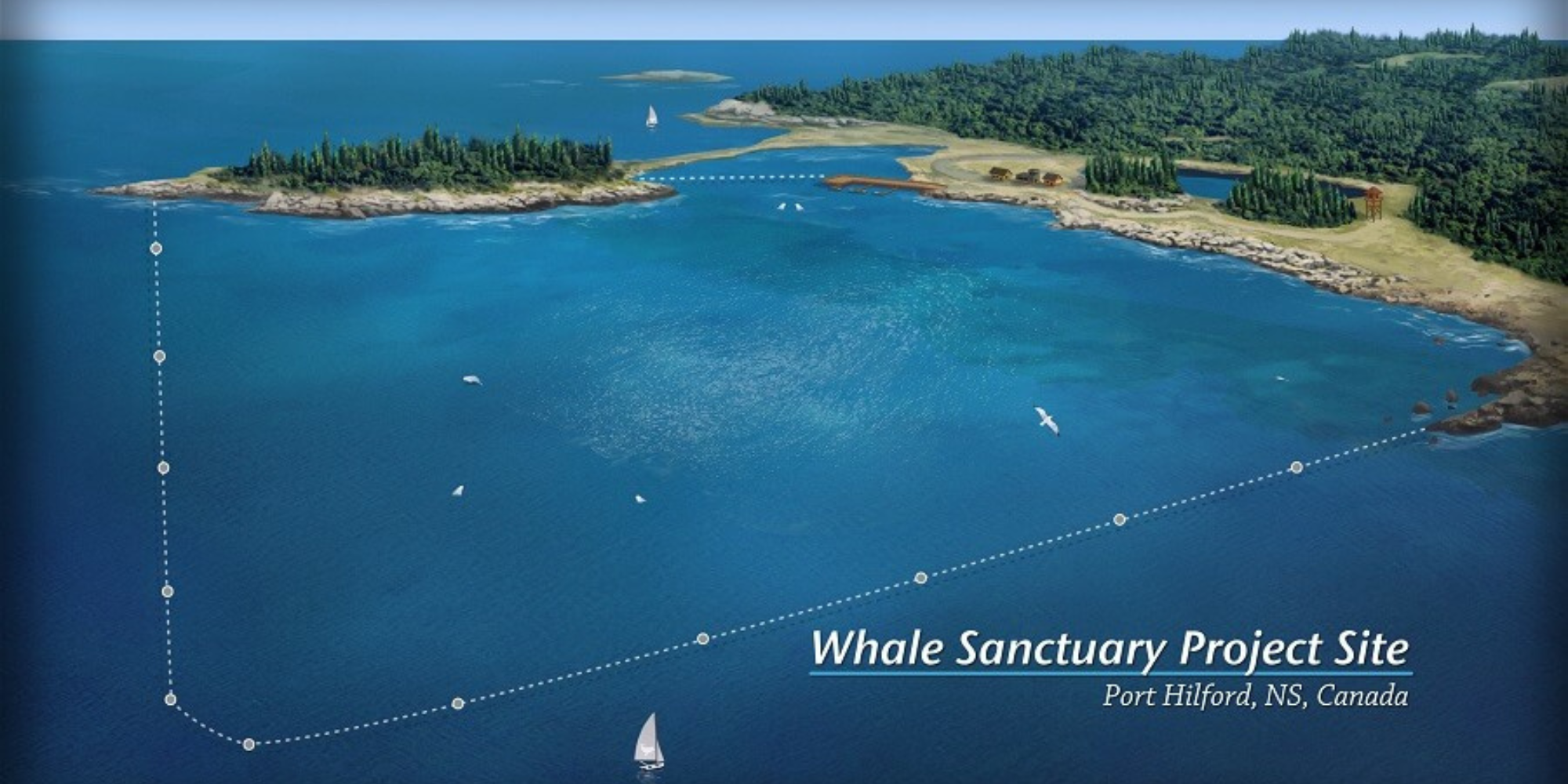

The Whale Sanctuary Project

This world class coastal sanctuary for whales and dolphins is being developed in Nova Scotia, Canada. Its vision is to have cetaceans living in an environment that maximises wellbeing and autonomy and is as close as possible to their natural habitat. It’s also being designed as a model for other sanctuaries to be built all over the world in years to come.

The idea for the sanctuary is very simple – there are already many sanctuaries for land animals like elephants, lions, and tigers, who are being retired from zoos and circuses. Now it’s time to provide such a sanctuary for whales and dolphins held in marine theme parks.

The Whale Sanctuary Project was incorporated in Washington DC in April 2016 as a non-profit.

After researching more than 130 locations in the U.S. and Canada, the Project selected Port Halford Bay in Nova Scotia as the best site to create a coastal sanctuary. The site is located on the ancestral lands of the Mi’kmaq people, a First Nations community, and their guidance and consultation has been a central part of the sanctuary development process.

The sanctuary will be as large as 50 football fields and 300 times larger than the biggest captive whale tanks.

Works have been ongoing over the past three years into site development, environmental studies and other types of surveys at the location, to get everything just right for the future sanctuary.

The Whale Sanctuary Project will be home to whales born into captivity who’ve never experienced life in the ocean with their family (the two species needing care are orcas and belugas). They need lifetime care so they can thrive in a natural setting as close as possible to what they’d experience in the open ocean.

If injured, stranded or recently captured whales are brought to the sanctuary, the plan is to treat and assess them, and every effort will be made to release them into the wild again. There are plans for an interpretative centre at the location and a viewing platform at the far side of the bay for people to view the whales from a respectful distance.

Find out more: The Whale Sanctuary Project

Sealife Trust Beluga Whale Sanctuary & Puffin Rescue Centre

Situated in the Vestmannaeyjar islands off the south coast of Iceland, the Sealife Trust Beluga Whale Sanctuary & Puffin Rescue Centre enjoys all the benefits of being in a relatively secluded and sheltered bay.

Its beluga whale residents are Little White and Little Grey, who travelled close to 10,000 kilometres via air, land and sea, from their previous home in a Shanghai Water Park. The belugas had originally been born in Russian waters before they were taken captive.

Klettsvik Bay, measuring up to 10 metres deep, gives significant space for the belugas to swim, dive and explore. There is room for up to 10 belugas at the sanctuary with hopes that other captive belugas will be rehabilitated there.

To keep the whales safe, the bay itself is enclosed by netting from the surface to the sea bed. There’s a special pontoon and care pool area to give access to the expert care team to look after Little Whale and Little Grey. There’s also a landside care facility at the sanctuary, and guest can visit seasonally from April to October (their visits help to fund the care for the belugas and puffins).

Find out more: Sealife Trust Beluga Sanctuary & Puffin Rescue

Aegean Marine Life Sanctuary

This sanctuary is currently in development to provide expert care and rehabilitation to sick and injured marine animals in and around the Greek Islands. It also will be home to formerly captive dolphins, who can thrive in a pristine natural environment.

The Aegean Marine Life Sanctuary (AMLS) is situated on the island of Lipsi in the Northern Dodecanese group of islands. After six years of thorough research, Vroulia Bay on the northwest of Lipsi was chosen as the preferred location.

The sanctuary bay has all of the natural conditions and stimuli essential for the physical and psychological wellbeing of bottlenose dolphins (the dolphin species most often held in captivity) along with other cetacean species.

The long fjord provides safe shelter from rough seas and the bay has ideal water conditions and sea currents to host marine animals in need of care. There’s even a shallow section that’s perfect for rehabilitation, along with deeper areas up to 40 metres in length.

A derelict building is being transformed into a redesigned rehab and research centre. A veterinary clinic, rehabilitation pools and general laboratory will all be present in the new sanctuary building.

The AMLS plans to have a viewing platform on a hill above the bay so visitors can observe the dolphins and other marine animals from a distance (preventing any possible disturbances to the species).

Find out more: Aegean Sanctuary

Deep dive…into Bowhead whales

Living exclusively in the Arctic region, the bowhead whale is the longest-living mammal on earth. It’s thought to live up to 200 years of age.

Situated in the harsh cold environment in northern Atlantic and Pacific waters, the bowhead whale is highly adapted to living in icy water. It is capable of breaking through sea ice up to eight inches thick, with its powerful body and big skull.

Bowhead whales keep warm with thick blubber layers, measuring up to half a metre thick. Entirely black except for the white front part of their lower jaw, bowhead whales can stay under water for up to an hour at a time, which allows them to swim under large ice floes.

Unlike most cetaceans, they don’t have a dorsal fin (it would awkwardly get in the way when swimming under ice!) They have extremely large heads, very stocky bodies and grow up to 18 metres long.

Bowhead whales are often spotted with scars on their bodies from them breaking ice, entanglement in fishing gear, and encounters with orcas. Scientists use these scars to identify and track individual whales.

Bowhead whales were initially thought to live around 100 years, based on the dating of stone harpoon tips recovered from the blubber of individual whales. However, newer research techniques suggest that they may live to be over 200 years old.

Scientists think the reason for the bowhead whale’s longevity, along with its slow growth rate and older age for reproduction, stems from living in the harsh Arctic environment.

Bowhead whales were hunted commercially in the early 1800s until the early 1900s. They were sought after because of the value of their oil and baleen – the fact that they are slow swimmers also made them an attractive target for whalers.

Like other whales, sound is vital for the survival of bowhead whales. They’re also highly vocal, possessing a wide variety of calls and sounds. Bowhead whales get their name from their very unique upper jaw and mouth which is shaped like an archer’s blow.

Where do bowhead whales live?

The species only lives in the polar Arctic waters of the northern hemisphere, and can mostly be found in shallow coastal water less than 200 metres deep, in amongst the sea ice. The whale moves further north in the Arctic region during the summer months as the sea ice melts.

Bowhead whales are usually found in regions including Canada, the U.S. (Alaska), Russia, Denmark (Greenland), Iceland and Norway.

Population

Whaling severely reduced the number of bowhead whales – from around 50,000 to 3,000 (estimated population in the 1920s). The population has recovered, somewhat, and is now thought to number 25,000 globally.

It is considered to be of ‘Least Concern’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The East Greenland-Svalbard-Barents Sea and Okhotsk Sea subpopulations, however, are classified as endangered.

What do they eat?

Bowhead whales are baleen whales, so they feed by opening their mouths wide and straining food from water through their baleen plates. Bowheads have the largest baleen plates of all whales (up to 5-6 metres long).

They eat copepods (a group of small crustaceans), krill and other zooplankton though there is evidence that they also eat some small fish species.

Threats to bowhead whales

Entanglement in fishing gear

Like other cetaceans, bowhead whales can become entangled in fishing gear which goes on to cause injury, fatigue, comprised feeding and sometimes even death. Around 12 per cent of the Western Arctic bowhead whale population show scars from entanglement in fishing gear, mostly from commercial pot-fishing gear.

Hunting

Sadly, the bowhead whale is one of the few whale species still subject to an ongoing aboriginal subsistence hunt in Russia, the U.S. (Alaska) and Greenland, managed by the International Whaling Commission.

Vessel strikes

Bowhead whales are at risk of vessel strikes and this is thought to be of increasing risk, as sea ice melts due to climate change and vessel traffic increases in Arctic waters.

Environmental change and pollution

Climate change and pollution are a threat to all whales and dolphins because of the loss of habitat as waters become warmer.

As their life cycle and habitat is so closely connected to life in the Arctic circle, bowhead whales are a species more affected globally by climate change and the melting of the polar caps. The effects include reduction in food sources and changes in migration patterns.

Plastics and micro plastics, along with chemical pollutants, entering into the water system are a serious threat to all creatures in our ocean.

With their great blubber stores, research shows that bowhead whales tend to accumulate more chemical contaminants in their bodies which affect their long-term health.

Bowhead whales, like other cetaceans, use noise to communicate and to locate prey. Increased noise pollution from vessels and other human activity interferes with this ability.

Natural predators

Orcas have been known to prey on bowhead whales. In a study, scars consistent with orca attacks were found on approximately eight per cent of subsistence hunted whales.

The WeWhale Pod Episode 12 - David C. Holroyd

Our guest for this episode of The WeWhale Pod is David C. Holroyd, dolphin trainer turned animal activist.

Manchester-born David shares the unexpected way that he became a dolphin show presenter and, soon after, a trainer in the 1970s. He also talks about the special connection he developed with two bottlenose dolphins, Herbie and Duchess, and why he has been campaigning for many years to make sure whale and dolphin shows around the world are shut down forever.

He also explains the Atlantean mind connection with dolphins and what that feels like.

Take a listen to the episode below:

David and his sister Tracy have written The Perfect Pair Dolphin Trilogy, a true story and a damning exposé of the captive cetacean industry. You can buy a copy at the links below:

The Perfect Pair Dolphin Trilogy

Thanks to Skalaa Music for post-production.

You can listen to previous episodes on our Podcast Page.

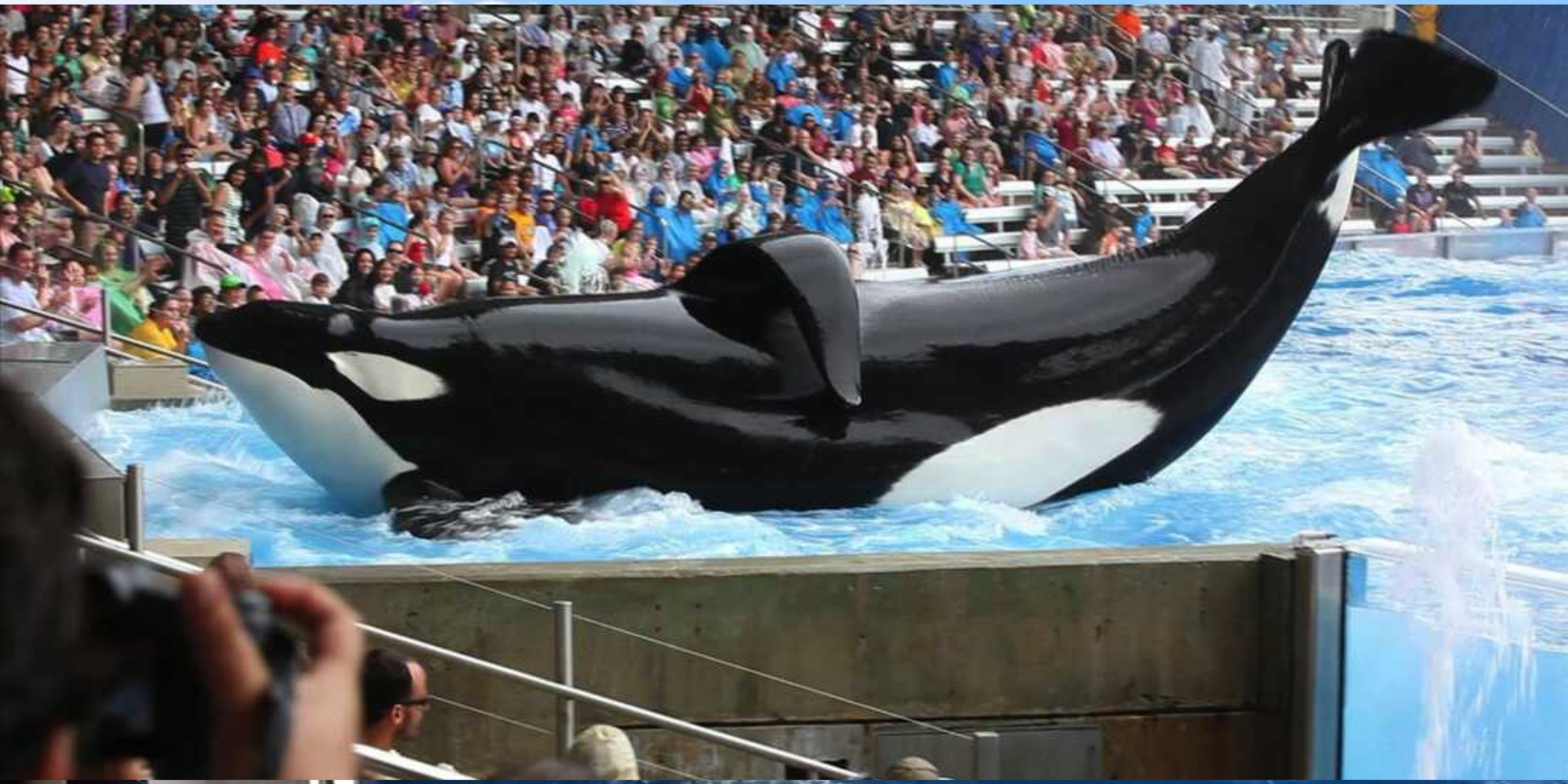

Whales That Made a Mark on the World: Tilikum

In our fifth and final blog on whales who’ve captured the attention of the world and the hearts of people, we take a closer look at Tilikum.

The male orca featured in the compelling 2013 documentary Blackfish, which did a huge amount to sway people’s opinions against keeping orcas in captivity in marine theme parks.

Tilikum’s story is a sad one, filled with so many instances where he suffered throughout his life. Ultimately, though, his story helped to create a ripple effect where marine theme parks came under greater scrutiny and public opinion has shifted.

Early life, capture and captivity

Tilikum was born in the waters off Iceland, likely sometime around December 1981. He was part of an extended pod of orcas, who stayed around Iceland. He would have been very close with his mother and other relatives, as orcas have very deep bonds with their familial pods.

In November 1983, when he was just two years old, he was taken from the water along with two other orcas (Nandu and Samoa).

Orcas don’t part easily with their children. As the abduction took place, male orcas in the group attempted to divert the humans while the female orcas and juveniles tried to swim the other way. Unfortunately a spotter plane relayed the whereabouts of the mothers and their offspring and that’s what led to the three orcas being taken.

Tilikum, Nandu and Samoa were confined for a year at Hafnarfjörõur Marine Zoo near Reykjavík, Iceland.

After being forcibly separated from his pod, Tilikum then had to endure being split up from the two other orcas. They were both sold to a facility in Brazil where Nandu died in 1988. Samoa was resold to SeaWorld, where she died in 1992 from a fungal infection, at the young age of 12.

Sealand of the Pacific

Tilikum was sold to Sealand of the Pacific, located on Vancouver Island in Canada. The plane trip from Iceland to the west coast of Canada was a long and presumably arduous one for the young orca. We can only imagine what that experience would have been like for an animal who belongs in the open water.

In Sealand of the Pacific, Tilikum was placed in a tank that was woefully inadequate for a whale of his size (and he was still growing at the time). The tank was just 30 metres by 18 metres with a depth of just under 11 metres.

His companions were two Pacific Northwest orcas, Haida II and Nootka IV. Tilikum was from Iceland so it should have been considered at the outset that there would be issues around communication.

Haida II and Nootka IV were also older female orcas who had become accustomed to each other and their own space, something that a three-year-old male orca was naturally going to disrupt.

The film Blackfish documents the bullying that was inflicted on Tilikum by the two whales and what created this harassment (lack of space, differences in communication, gender and age).

It also shows that when Tilikum did not perform to the satisfaction of the trainers, food was deprived from all three orcas. This obviously created an unbearable tension between the three captive animals.

Often times, Tilikum was forced to retreat into a smaller medical pool, to avoid being physically raked by the other two (raking is when whales use their teeth against the skin of another whale). Trainers would keep him there for his own protection for extended periods of time.

In February 1991, a young trainer at the aquarium, Keltie Lee Byrne, slipped and fell into the whale pool. Witnesses said she screamed and panicked when she realised one of the whales (later identified as Tilikum) was holding her foot in his mouth and dragging her underwater.

Rescue attempts were unsuccessful as the whales initially refused to let Keltie go, and when she was retrieved from the water, it was sadly too late. The 20-year-old’s death was later ruled an accident.

No fatal attacks on humans by orcas had ever been recorded before this. And, tragically, this was not the be the last one involving Tilikum.

After the birth of a calf to Haida II, Tilikum was kept in the smaller medical pool 24 hours a day. Even when the gate to the main pool was left open and Tilikum ventured out, he would quickly get chased back by the two female orcas, who felt protective of the calf.

For weeks before he moved to SeaWorld Orlando in 1999, he stayed confined in this small space measuring seven metres wide and 3.6 metres deep. At the time, he was six metres long, meaning there was barely enough room for him to turn around.

SeaWorld

It had become clear that Sealand of the Pacific could no longer look after Tilikum (incidentally, it eventually closed for good in November 1992). And he was an attractive prospect to other marine theme parks because of his ability to sire lucrative orca calves.

So, in 1992, Tilikum and Nootka IV were sold to SeaWorld Orlando, and Haida II and her baby Kyuquot were sold to SeaWorld Antonio. Tilikum faced another plane trip, this time from the west coast of Canada right down to the south east tip of the United States.

He would go on to spend 24 years at SeaWorld, in a tank that was much smaller and nothing like the expanse of sea he swam in off Iceland. Tilikum was well known for his large size, measuring 6.7 metres long and weighing in at 11,800 lbs (5.3 tonnes). He was twice as large as the next orca being held in SeaWorld Orlando.

Tilikum is said to have sired 14 calves in the years he was at SeaWorld. Blackfish reveals how he was trained to roll onto his back so that employees could masturbate him with a gloved hand and then collect semen to forcibly impregnate female orcas with.

During his lifetime, he was bred a total of 21 times with 11 of his offspring dying before he did.

Tilikum was trained to perform as part of the Shamu show but aside from those shows, he lay listlessly at the surface or the bottom of the tank for extended periods.

Unsurprisingly, the effects of captivity, bullying, and lack of stimulation showed themselves. He sometimes displayed aggression towards humans and he bit the gates and concrete sides of the tank (causing damage to his teeth). PETA reported that he was charged and raked by other orcas so severely that he sometimes bled, shivered and needed to be kept out of shows.

The orca was unable to swim any meaningful distance or dive. It’s calculated that he would needed to have swum the circumference of the tank more than 1,900 times in a single day to match the distance he’d have swum in the wild in a single day.

In 1999, Tilikum again came under the spotlight in regard to a human’s death. A 27-year-old man, Daniel Dukes, stayed in the SeaWorld park after hours and entered into the pool.

In the morning, he was found dead on Tilikum’s back and an autopsy concluded that he had drowned. There was evidence, though, of numerous injuries on his body.

Death of Dawn Brancheau

On 24 February 2010, Tilikum was performing as part of the ‘Dine with Shamu’ show. This live performance involved some guests dining downstairs and seeing orcas through an underwater window.

Trainer Dawn Brancheau (who worked at SeaWorld for 15 years) was standing alongside the pool, interacting with Tilikum.

Reports on what happened next differ. Some say the 40-year-old slipped and fell into the pool while others (including SeaWorld) say that Tilikum grabbed her by her long ponytail and dragged her under the water.

It quickly became clear that Tilikum was not going to let Dawn go and kept her from reaching the surface. A sense of shock and dread took over the Shamu stadium. Onlookers at the underwater window and those seated in the auditorium were ushered away from the awful spectacle that lay before them.

As Tilikum swam back and forth between pools with Dawn in his mouth, SeaWorld workers tried to save her. Tilikum was captured into a net but still refused to let her go.

A rising platform was used to remove him from the water and eyewitness reports say that even after Tilikum was lifted, Dawn still could not be freed from his mouth until employees pried open his mouth. Paramedics worked on the trainer but it became clear that Dawn had died while in the water. A later investigation showed that she died from multiple traumatic injuries and drowning.

Dawn’s death drew international media headlines. Concerns were raised over how safe it was to work so closely with wild animals, and also what led Tilikum to act so aggressively towards a person.

There was talk, in the aftermath, of euthanising Tilikum but ultimately that wasn’t the course taken.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) carried out an investigation in 2010 into safety regulations at the SeaWorld facility.

The investigation slapped SeaWorld with safety violations and $75,000 in fines. It also determined that SeaWorld had wilfully violated employee safety by putting their trainers in the water in close interaction with the captive orcas.

Tilikum returned to performing a year later.

Blackfish

In July 2013, the documentary Blackfish was released. It particularly got traction after CNN started to air it in the U.S. Viewers were drawn in by the shocking, never-before-seen footage, and interviews with trainers and experts. Several former trainers spoke up about what they saw as lack of safety consideration for those working at the park, and about what they’d observed with Tilikum over the years.

The film centred on the attack on Dawn, but focus was also dedicated to going back in time to explain exactly what Tilikum’s life had been like since he was taken from his family. The picture painted is that Tilikum had become affected by psychological trauma, perhaps even psychosis, due to what had happened to him.

You can read more about this in a PETA report on the effects of captivity on Tilikum and orcas generally at SeaWorld.

Tim Zimmerman, a writer with Outside magazine and producer on Blackfish, said, “I think that’s the most amazing thing that comes out of Tilikum’s story. He killed three human beings. And yet when you learn about his life story, he does become the victim and you do sympathise with him.”

Blackfish also featured other attacks on trainers (one attack shown involves trainer Ken Edwards being repeatedly pulled underwater by an orca in an incident that lasts 12 minutes).

The death of trainer Alexis Martínez at Loro Parque in Tenerife is also detailed in the documentary. He died due to grave injuries inflicted by the orca Keto.

The film sparked huge reaction and a groundswell of support for the plight of whales kept in captivity. It also reached a wider audience when it was added to Netflix in late 2013.

After the documentary’s release and following protests by PETA and other groups, attendance at SeaWorld theme parks dropped. The company’s profits fell (rumoured to be in excess of $10 million), it lost promotional deals and had to cut jobs.

SeaWorld had chosen not to participate in Blackfish and has disputed many elements of the film, saying it conveys falsehoods and manipulates viewers emotionally.

See the Blackfish trailer:

Tilikum’s death

Tilikum continued to be mostly kept in a medical pool, to keep him from attacks from other orcas. Apart from performing in shows, he is said to have been listless, again lying at the bottom or top surface of the water.

On 8 March 2016, SeaWorld announced that Tilikum’s health had deteriorated and he was being treated for a bacterial lung infection. Just a week later, the company announced that it was going to stop breeding orcas in captivity, meaning that the orcas currently in the marine theme parks would be the last.

Animal activists welcomed the news but said the company should organise for the rehabilitation and release of the whales it currently has in captivity.

In January 2017, at the estimated age of 36, Tilikum died of bacterial pneumonia.

Lisa Lange, senior vice president for PETA, summed it up well at the time of his death, “From the moment, he was taken from his ocean family, his life was tragic and filled with pain, as are the lives of the other animals who remain in SeaWorld’s tanks and exhibits.”

Check out previous blogs

Whales That Made a Mark on the World: The Thames Whale

Whales That Made a Mark on the World: Keiko

Deep dive...into Atlantic spotted dolphins

Fast swimmers who are often active at the ocean’s surface, Atlantic spotted dolphins are found across most of the warm Atlantic.

Unsurprisingly, they get their name from their distinctive spots! When they’re born, they start out grey, like other dolphins. But after a year or two, they develop speckles which later turn into mottled spots.

By the time Atlantic spotted dolphins mature into adults, they appear with light spots on their dark backs and darker spots on their pale bellies. Interestingly, the Atlantic spotted dolphins who live in the Gulf Stream, far offshore, often lack spots.

The species (Stenella frontalis) weighs in between 220 – 320 pounds and are around five to seven feet long. The dolphins have bulky heads and bodies, and long, narrow beaks. Their dorsal fin is long and curved.

The cetaceans usually form groups of between 5 and 50 individuals but they are sometimes spotted travelling in large pods of up to 200. They’re extremely social and are also very playful. Atlantic spotted dolphins can be seen performing acrobatics, riding the bow waves of boats and/or surfing the waves behind them.

As well as being a fast swimmer, the Atlantic spotted dolphin is a great diver. It can dive for up to 60 metres and has been recorded holding its breath for up to 10 minutes.

Atlantic spotted dolphins have been extensively studied by the Wild Dolphin Project in the Bahamas since 1985. They use surface and underwater photography to identify individual dolphins.

Every field season, known dolphins are re-identified, new dolphins including calves and immigrants are identified, and the losses of animals are documented too.

The research project also monitors reproductive and health status, and social associations. Find out more on the Wild Dolphin Project website.

The species is listed as ‘Least Concern’ on the IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species.

Where do Atlantic spotted dolphins live?

The species is found across most of the warm Atlantic (warm, temperate and tropical waters) and usually keeps within 360 kilometres of the shore. Sometimes, it can be seen in deeper oceanic waters.

Atlantic spotted dolphins are often seen in the waters off the Bahamas, the Azores, the Canary Islands, Brazil and off the U.S. East Coast (from the Gulf of Mexico to Massachusetts). In the Bahamas, the Atlantic spotted dolphins spend a lot of time in shallow water on sandbanks which makes them very accessible to research.

Check out this underwater video of Atlantic spotted dolphins in Tenerife taken on the WeWhale vessel ‘Esiel’.

What do they eat?

Atlantic spotted dolphins often work as a team to catch prey together. They eat small fish, invertebrates (molluscs, crustaceans etc.) and cephalopods (squid, octopus, cuttlefish etc.). The species has been observed using their beaks to dig into the sand on the ocean floor to catch hidden fish.

Threats to Atlantic spotted dolphins

Entanglement

One of the main threats to Atlantic spotted dolphins is entanglement in fishing gear. This can go on to cause injury, fatigue, comprised feeding and sometimes even death.

Vessel strikes

The species is at risk of vessel strikes throughout their range but the threat is higher in areas with busy ship traffic.

Environmental change and pollution

Climate change and pollution are a threat to all whales and dolphins because of the loss of habitat as waters become warmer.

Plastics and micro plastics, along with chemical pollutants, entering into the water system are a serious threat to all creatures in our ocean.

Atlantic spotted dolphins, like other cetaceans, use noise to communicate and to locate prey. Increased noise pollution from vessels and other human activity interferes with this ability.

Hunting

There is no commercial hunting of Atlantic spotted dolphins but there have been recorded instances of the species being hunted and killed in the Caribbean, South America, West Africa, and other offshore islands, for food and bait. .

Natural predators

As with other dolphin species, Atlantic spotted dolphins are sometimes the prey of orcas and large sharks.