The WeWhale Guide to Whale Watching Destinations Around the World

If you’ve ever gotten to see whales in their natural habitat, you’ll know what an exciting, uplifting and memorable experience it is. And if you haven’t yet gone whale watching, you need to get it on your bucket list asap!

Combining an overseas trip and a whale observation experience makes for a really special holiday. Whether you’re a newbie to whale watching or it’s something that, pardon the pun, regularly floats your boat, we’ve put together 12 of our top whale watching destinations around the world (it was hard to pick just 12 as there are many great locations to choose from!)

Read on to find out why these are such great locations to see whales in the wild, what species you can see and the best time of year to make your trip.

Europe

Tenerife, Canary Islands

In 2021, the Tenerife La Gomera area was declared the first Whale Heritage Site in Europe, reflecting its position as one of the world’s top-rated whale watching destinations and also guaranteeing that whale watching is carried out in a responsible and habitat-friendly manner.

The Tenerife La Gomera area is a marine strip between the two islands of La Gomera and Tenerife (off the west coast). Long before it was named a Whale Heritage Site by the World Cetacean Alliance, it was designated a Special Conservation Area by Tenerife authorities, helping to protect the many animal species in the area and its biodiversity.

Most whales and dolphins can be sighted just 20 minutes off the coast of the island. As the Canaries are volcanic islands, there is great depth just a few metres off the coast for cetaceans to enjoy and to thrive in.

A colony of more than 500 short-finned pilot whales live year-round in these waters. They have unique hunting behaviours which haven’t been observed elsewhere, including deep, high-speed dives to chase and capture squid.

More transient in the waters (and therefore less frequently spotted) are orcas, sperm whales, fin whales, humpback whales, blue whales, sei whales and Bryde’s whales, Blainville’s beaked whales and Cuvier’s beaked whales. You never know when they will pop up their heads in this region’s waters, making Tenerife an exciting place to go whale watching.

When to go?

The mild climate that the Canaries enjoys makes it a year-round whale watching destination.

Húsavík, Iceland

The town of Húsavík in the north of Iceland has really pioneered whale watching in Iceland and we think offers a more unique experience than the more well beaten path to the capital city, Reykjavík.

The cold waters off the coast of Iceland play host to a biodiverse marine life, particularly during the summer months when a range of whale and dolphin species use it as a feeding ground.

Húsavík is located in the beautiful Skjálfandi Bay, where the most commonly spotted whales are humpback whales and minke whales, with sperm whales, fin whales and orcas also putting in appearances. Even the largest animal on the planet, the blue whale, has been sighted in the bay.

When to go?

The best time to spot whales and the most comfortable time, temperature-wise, for a whale observation experience is the late spring/summer/early autumn (April to October). Whale watching experiences in the winter are less frequent but they’re also less crowded and even come with the chance of seeing the Northern Lights.

West Cork, Ireland

The coastal waters off the southwest of Ireland are a summer feeding ground for three types of baleen whales: minke whale, fin whale and humpback whale. This makes whale watching in Ireland some of the best whale watching in Europe, with West Cork being a particular draw for whale and dolphin watching enthusiasts.

Whale watching companies are centred in villages including Baltimore, Courtmacsherry and Union Hall.

To date, 24 species of the world’s cetaceans have been recorded in Irish waters so you’re also likely to see plenty of dolphin species while out searching the horizon for whales.

When to go?

Minke whales usually start arriving off the Irish coast in March and can be seen well into winter (till November). Fin whales traditionally arrive in the late summer/early autumn and humpbacks are a bit less predictable, often showing up in late spring/early summer (April-June) but also known to make appearances later in the summer and into the early days of autumn.

Winter is also a good time to spot whales although it is obviously a colder experience to be out on a whale watching boat during this time and sea conditions can impact if and when tours go out.

Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar is one of the most extraordinary habitats for marine mammals in the world. It connects the Atlantic Ocean with the European Mediterranean Sea and at its narrowest point, it’s only 13 kilometres wide.

The large food supply in the Strait, which is naturally maintained by the opposing currents, ensures that whales and dolphins stay there despite the noise levels from vessel traffic. Also cetaceans often migrate from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea through the Strait in order to reproduce in a protected environment.

The fishing of tuna attracts a resident group of orcas during summer months. Sperm whales, fin whales and pilot whales are also frequently spotted in the Strait of Gibraltar

When to go?

Pilot whales, along with dolphins, stay in the area throughout the year but other species are more seasonal visitors. Orcas follow the tuna during the summer months so June to August is the best time to visit if you wish to catch a sight of them.

Sperm whales are usually seen between April and August, with fin whales being less predictable when they show up in the Strait.

Australasia

Kaikōura, New Zealand

Located on New Zealand’s south island, Kaikōura is an incredibly scenic town and one of the best places to experience whale watching in the world.

The reason why? The Kaikōura Canyon, just off the coast, contains deep trenches and underwater canyons where whales can breed undisturbed. Sperm whales usually inhabit the deep ocean and are rarely seen along coastlines unless there are offshore canyons.

So it’s no surprise then that sperm whales are the primary residents in this region and the species you’re most likely to see on a whale watching tour in Kaikōura. After sperm whales, orcas and humpback whales are most likely to be spotted, and less frequently, you might spot Southern Right whales on their migration, minke whales and long-finned pilot whales.

When to go?

Sperm whales are resident off Kaikōura all year round. Orcas can be seen from November to March (some estimates say they’re usually seen at least two to three times a month during that period) and humpback whales are usually spotted in June and July.

Temperature-wise, it’s warmer to whale watch from October to March which is the southern hemisphere spring and summer. But if you wrap up warm, you can have a great experience in the winter time (June-August).

Hervey Bay, Australia

The town of Hervey Bay in Queensland has been a centre for humpback whale watching for decades and in 2019, it was jointly named the first Whale Heritage Site in the world.

Hervey Bay is an important and protected stopover site for migrating humpback whales, making their way along the eastern coast of Australia.

The waters off Hervey Bay are part of the Great Sandy Strait Marine Park and just a short distance out to sea from the town is the biodiverse Fraser Island (well worth a visit if you’re planning a visit to Hervey Bay).

The humpbacks who visit the bay tend to stick around a while (10 days on average) which means there’s a very good chance of seeing them once they arrive offshore.

It’s thought that 20,000 humpback whales migrate through the region every year with around 8,000 of them using the calm waters of Hervey Bay to rest and nurse their new-born calves before continuing on their migration.

A certain albino humpback called Migaloo has been spotted in this neck of the woods. Also spotted in Hervey Bay are minke whales, Southern right whales and Bryde’s whales, along with a large range of dolphin species.

When to go?

June to November is when the humpback whales visit Hervey Bay and even within that period, early August to late September is the optimum time to see them.

North America

Baja California, Mexico

The most northernmost of the Mexican federal entities, Baja California is just across the border from the U.S. It neighbours the Golden State, California.

Sandwiched between the Pacific Ocean to the west and the Sea of Cortez to the east, Baja California is an incredibly rich area for marine mammals, particularly whales.

The whales who frequent this region have migrated south from the freezing Alaskan waters to enjoy the warm welcoming waters off Mexico. It’s here that they mate, give birth and raise their young. On the Pacific coast, the most common species are the humpback whale and grey whale while the Sea of Cortez plays host to humpbacks, orcas and fin whales.

It’s also possible to see sperm whales, minke whales, blue whales and pilot whales though they are more elusive in these waters.

Grey whale observation in Baja California Sur is quite the experience as the whales are very friendly, curious and approach boats seeking out interaction from humans. This is particularly common in Magdalena Bay.

When to go?

Whale watching is a year-round activity in Baja California but if you’re interested in particular species, you can time your trip more specifically.

Grey whales are usually spotted from late December to April, with peak months in February and March. These months are also the best months if you’re looking for blue whales and orcas. Humpback whales are the most commonly spotted whales in Baja California Sur and are sighted from December to April.

Vancouver Island, Canada

You’re spoilt for choice when it comes to species of whales found off Vancouver Island in British Columbia (on the west coast of Canada). Minke whales, grey whales, humpback whales and orcas are found at different times of the year.

There are two resident orca populations found on Vancouver Island that never mingle with each other. One group lives close to the town of Victoria and another group lives further north, patrolling the Johnstone Strait.

In addition, there’s also a transient orca group of 160 whales which travel much further than the resident pods. Vancouver Island is one of the most studied areas in the world when it comes to understanding more about orca whales and the quaint little village of Telegraph Cove on the east coast is one of the best places to go and experience orcas in the wild.

Pacific grey whales migrate north along the west coast of Vancouver Island and many of them stop off to rest in the calm bays and to feed. Humpback whales are usually found to the north of Vancouver Island.

Tofino, a small town on the west coast, is a great place to spot grey whales on their migration and you might also be fortunate to see orcas, fin whales, minke whales and humpbacks here. It’s also a fantastic place to surf, if you fancy catching a wave!

When to go?

March and April are the best times to spot grey whales but they can and do show up a little later into the year. Humpback whales are there during the summer months (May to September).

As a general rule, May to October is the period when orcas are most often spotted off Vancouver Island but that can be narrowed into a peak period of July to mid-September, especially if you’re heading to northern Vancouver Island.

Central and South America

Península Valdés, Argentina

Located in the heart of Patagonia, Península Valdés is a very significant region for the conservation of marine mammals. It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999.

The peninsula includes about 400 kilometres of shoreline and reaches more than 100 kilometres eastwards into the South Atlantic Ocean. The calm gulfs located along the peninsula are key breeding, calving and nursing areas for the Southern right whale.

The species’ population suffered greatly during the years of commercial whaling but thankfully has been increasing in numbers in the past 40 years, thanks to conservation efforts. There has been recent concern, though, that climate change will negatively affect that progress.

The Península is also well known for orcas who beach themselves on purpose, in order to catch and kill beach-dwelling sea lion pups. The orca aims to successfully catch its prey and then catch the next wave off the beach, using the steep and pebbled beach to roll back to the water.

To view this behaviour, tourists head to a lookout point at Punta Norte during a very short window of time each year and keep their fingers crossed they get to see this unique behaviour.

When to go?

Southern right whales are present in different waves of migration off the coast of Península Valdés from June to December, with the best time to view them in August to October. The peak time for orcas to hunt on the beach at Punta Norte is a 10 to 15 day period, usually in March or April.

It’s also possible to view orcas off the coast but the timing of this can be unpredictable (they are generally around in the waters during their migration between September and April).

Uvita, Costa Rica

Costa Rica in Central America is a fantastic destination to experience whales, with the laid back beach town of Uvita the main place to head to. The town is surrounded by the Parque Nacional Marino Ballena (Marine Whale National Park), created in 1990.

The beach shoreline near Uvita forms into a spit, that looks just like the fluke of a humpback whale. It’s known as ‘The Whale’s Tail’.

One of the reasons why Costa Rica is such a great whale watching destination is because it enjoys two whale watching seasons in a year (most locations around the world only have one season). Northern hemisphere humpback whales head south to the warmer waters of Central America between December and April.

Then between July to mid-November, the Southern hemisphere humpback whales head up from their base in the Antarctic to enjoy the warmer waters too.

When to go?

The whale watching season is almost all year-round in Uvita but the chances are highest between December and April and then again from July to mid-November e.g. May and June are months you are a lot less likely to see humpbacks.

A Whale and Dolphin Festival is celebrated each year at the end of September in Uvita so it’s well worth timing your visit to take part in this!

Antarctica

Not the easiest (or cheapest!) destination to get to but if you’re looking for a real whale watching adventure, this is definitely one to consider.

Whale watching in Antarctica usually takes place aboard small zodiac boats but because you’re based on a larger tourist ship (or cruise ship), you’ll be able to cover more ground and have more opportunities for whale sightings.

Up to eight different whale species are encountered in Antarctica – humpbacks (the most sighted), minke whales (the second most), orcas, sperm whales, Southern right whales, sei whales, Antarctic blue whales and fin whales.

It’s a beautiful setting to observe and appreciate whales, with statuesque icebergs in the background, amazing clear skies and a peaceful and quiet environment in this unpopulated region.

Whales are found all around Antarctica but hotspots include the Drake Passage crossing, Wilhelmina Bay (sometimes known as ‘Whale-mina Bay’ due to the number of whales that can be seen) and the Lemaire Channel.

When to go?

The best time to spot whales in Antarctica is February and March, which is just after the southern hemisphere summer when the animals have been busily feeding (after their long migration back).

That means they are usually full of energy, in a playful mood and most likely to be curious about human activity nearby.

Africa

Hermanus, South Africa

Close to Cape Town at the bottom tip of Africa, Hermanus is a brilliant place to observe Southern right whales. They can be spotted very close to land, meaning you can choose from land-based or boat-based whale watching.

The whale species migrates from Antarctica every year, heading northerly into warmer waters to breed and give birth. It’s also possible to see other whale species including humpbacks and Bryde’s whales.

When to go?

Most sightings of Southern right and humpback whales happen between June and October with the best months being August to early October.

Hermanus hosts an annual whale festival at the end of September/start of October each year, attracting around 150,000 people. And interestingly, the city employs a ‘whale crier’ whose main job is to blow a horn to alert people whenever a Southern right whale is spotted!

The WeWhale Pod Episode 5 - Alex Lewis

Our guest for this episode of The WeWhale Pod is Alex Lewis.

Alex is a co-founder of Fins and Fluke, a cetacean advocacy non-profit established in 2012 which particularly focuses attention on the plight of captive whales and dolphins.

Amongst the topics, Alex talks about how watching the documentary The Cove moved her to become an anti captivity activist for whales and dolphins and how social media is really helping to spread the word about the plight of captive cetaceans.

She also chats about how marine parks in the U.S. are seeing their entry numbers drop, as public sentiment continues to change. And she says, “I cannot wait to see them close their doors forever!”

You can find out more about Fins and Fluke’s work on Facebook and Instagram. Thanks to Skalaa Music for post-production.

Take a listen to the episode below:

And you can listen to previous episodes on our Podcast Page.

Deep dive...into Minke whales

The minke whale is the second smallest member of the baleen family, growing to a maximum of 10 metres long and weighing up to nine tonnes.

The scientific name for the Common minke species, Balaenoptera acutorostrata, translates to ‘sharp snouted winged whale’. And the name ‘minke’ comes from a Norwegian novice whaling spotter called Meincke, who is said to have mistaken a minke whale for a blue whale.

The minke whale is also a member of the rorqual family of whales (these whales have baleen, a dorsal fin and throat pleats). Minke whales are usually quite solitary, spotted on their own or in small groups of two to three, although it is possible to see them in larger groups (usually when they are feeding).

The species is recognisable from its slender and streamlined body, its baleen pleats that expand during feeding and its narrow, triangular rostrum (upper jaw) which is proportionally shorter than ones in other rorquals.

Its colouring is black to grey on top with white below, with two areas of lighter grey on each side of the body – one behind the flippers and the second one around the tall dorsal fin.

Minke whales are found in two distribution groups – one in the northern hemisphere and one in the southern. Each of the groups migrate to their respective polar regions to feed for several months of the year before returning to more temperate waters.

Northern hemisphere whales have a distinctive white band located in the middle of their flippers, while the southern variety doesn’t have this. And southern hemisphere minke whales tend to be slightly larger in size than the northern species and are referred to as Antarctic minke.

There is an unofficial sub-species of the Common minke, called the dwarf minke whales. As you’d expect, it’s smaller in size.

Dwarf minke whales grow to seven to eight metres long and weigh up to 6.3 tonnes. Their colouring is slightly different also with a bright white path on the upper part of their pectoral fin which extends up around the shoulders and back. They also have darker shading on their head compared to their bigger counterparts.

The estimated life span of the minke whale is 50 years old.

Behaviour

Minke whales are more difficult to spot in the water, compared to other whales, because they send out a small and weak blow from their two blow holes. They also surface from the water snout-first and don’t raise their flukes out of the water when they’re diving (they roll their back and body above the surface of the water before taking a deep dive).

The overall effect is of a graceful creature gliding through the water and is a beautiful sight to behold.

Minkes can stay submerged for up to 15 minutes before they need to come back up for air. They’re often spotted spy hopping, especially in icy areas, and they’re known to be curious creatures, with some individuals approaching vessels and swimming alongside them. Minkes are fast swimmers, capable of reaching speeds up to 30-38 kilometres per hour.

Some interesting research has been carried out into the calls of minke whales. A study by the University of California, published in 2022, identified four key Antarctic minke whale calls.

The most common was the rumble, a short call lasting just over one-tenth of a second and said to sound like pulling up a zipper. The three others are named the growl, boom and the downsweep (this had been reported back in the 1970s but was mistakenly attributed to the common minke whale).

The study was also able to connect the calls to particular types of behaviour and times of day or night when they take place.

Where do minke whales live?

The species is found in oceans all over the world, in polar, temperate and tropical areas (though they’re not spotted frequently in the latter).

They feed most often in the cooler waters at higher and lower latitudes, with some minke whales migrating long distances each year to warmer waters and some opting to remain closer to their feeding grounds.

Research shows that older male minkes are more commonly found in the polar regions during the summer feeding season. Mature females also travel into these areas but are more likely to stick closer to coastal waters instead of the open ocean.

Dwarf minke whales are found almost exclusively in the southern hemisphere, most frequently in areas off Australia, South America and South Africa.

Population

Whalers in the 19th and 20th centuries initially overlooked the minke whale as a target species as it was considered too small and too fast to be worth hunting. But when the larger species became severely depleted and tricky to locate, attention turned to the minke.

Whaling practices have had an impact on population, particularly since whaling started to focus on them more in the late 1960s and 1970s onwards. But over the whole period of whaling, minke whale numbers have been less impacted when compared to other species such as the grey whale, blue whale or humpback whale.

Some experts say the minke whale may have had some advantages in the early years of whaling as there was less competition for food as other whale species numbers reduced in numbers.

Over the past 50 years though, the minke whale has been on the radar of countries that continue to commercially hunt and kill whales. Japan, Norway and Iceland target minkes as part of their catch (with quotas from the International Whaling Commission). In February 2022, Iceland indicated that its whaling would come to an end in 2024 as demand for whale meat has dwindled.

Greenland has catch limits from the International Whaling Commission for aboriginal subsistence whaling, and they include minke whale in these catches.

Estimates of the global minke whale population vary from 500,000 to 1 million. About three quarters of the species are located in the southern hemisphere, with the next biggest population group in the North Atlantic and after that, the north Pacific Ocean.

Overall, the Common minke is designated as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List for Threatened Species. The Antarctic minke is listed as Near Threatened on the list.

What do they eat?

Minke whales are side lungers when it comes to feeding – they open wide and gulp in large amounts of sea water and food. Their baleen plates filter the prey from the water, which drains back out.

Antarctic minke whales feed almost exclusively on krill while the Common minke eats a wider range of food (plankton, crustaceans, anchovies, dogfish, eels, herring, salmon, cod, mackerel and more). Common minkes off Greenland eat krill, like their Antarctic counterparts.

Threats to minke whales

Entanglement in fishing gear

Like other whales, minkes can become entangled in fishing gear which goes on to cause injury, fatigue, comprised feeding and sometimes even death.

Minke whale bycatch has been observed to be particularly high off the coasts of Korea and Japan.

Vessel strikes

Minke whales are at risk of vessel strikes throughout their range but the threat is much higher in coastal areas with busy ship traffic. Trans-polar shipping routes are expected to become busier as Arctic sea ice continues to melt year-on-year.

This will have an impact on whales in terms of increased vessel strikes, increased noise and pollution.

Whaling

As discussed earlier in the article, whaling is still a threat for minkes as several countries continue to hunt and kill the species.

Environmental change and pollution

Climate change and pollution are a threat to all whales and dolphins because of the loss of habitat as waters become warmer. Minke whales are particularly vulnerable to the loss of ice in the polar regions, as it’s a vital feeding ground for the species.

Plastics and micro plastics, along with chemical pollutants, entering into the water system are a serious threat to all creatures in our ocean.

Minke whales, like other whales, use noise to communicate and to locate prey and increased noise pollution from vessels and other human activity interferes with this ability.

Natural predators

Orca are the only known natural predator of minke whales. Attacks have been observed more frequently in the southern hemisphere.

Check out this video of a curious minke whale in Portuguese waters:

The WeWhale Pod Episode 4 - Femke den Haas

Our guest for this episode of The WeWhale Pod is Femke den Haas, Indonesia Campaign Director for Ric O'Barry's Dolphin Project.

Amongst the topics, Femke talks about being fascinated by dolphins and any creatures living in the ocean whilst growing up, her work with wildlife rescue groups around the world and the important rehabilitation and rescue work for dolphins taking place in Indonesia.

You can find out more about Femke and her colleagues' work on the Dolphin Project website. Thanks to Skalaa Music for post-production.

Take a listen to the episode below:

And you can listen to previous episodes on our Podcast Page.

Deep dive...into Humpback whales

Humpback whales make one of the longest migrations of all animals, with some individuals travelling up to 8,000 kilometres between their feeding and breeding grounds.

Part of the baleen whale group, humpback whales have the scientific name ‘Megaptera novaeangliae’. The first part translates to ‘big-winged’, in reference to the whale’s long pectoral fins. And ‘novaeangliae’ is the Latin word for ‘New England’, which refers to the location where European whalers first encountered the species.

The descriptor ‘humpback’ comes, unsurprisingly, from a small hump in front of the whale’s dorsal fin. The hump becomes apparent when the creature raises and bends its back in preparation for a dive underwater.

Humpback whales can grow to 18 metres long (females tend to grow slightly longer than males) and they can weigh in at a whopping 40 tonnes (40,000 kg).

Their appearance is mostly grey or light black and individuals have different amounts of white on their bellies, the undersides of their flukes (tails) and on their pectoral fins. These markings help researchers to photo identify and track individual humpback whales over time.

It’s known that Southern hemisphere humpbacks tend to have more white markings, particularly on their bellies and flanks, than the Northern hemisphere humpbacks have.

The whale’s fluke is noticeably wide (up to 5 metres) so that’s often the part of the body that’s first spotted in the water by researchers and whale watchers. The fluke has a serrated pattern along its edge.

Humpbacks spend most of their time near coastlines, which is where they find their food (tiny shrimp-like krill, plankton and small fish).

The species has a life expectancy of 80 to 90 years. Females produce a single calf every two to three years on average, with their offspring staying with mum for up to a year after weaning. Mothers are protective of their calves, swimming very close to them and staying tactile through pectoral fin touch.

These pectoral fins are amazing tools – they grow up to around a third of the whale’s body length and are highly manoeuverable. The species uses their fins for swimming, hunting (they slap the water) and researchers believe they may also use them to regulate body temperature.

Where do humpback whales live?

Humpbacks are found in oceans all over the world, with major populations found in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and in the Southern and Indian oceans.

In the northern hemisphere, whales feed in the colder polar areas between June and October before heading south to breed in warmer waters in the months between December and April.

In the southern hemisphere, the populations feed around the Antarctic between November and March and migrate north towards the equator where they mate and give birth between July and October.

The migrations are long each year – up to 8,000 kilometres – and the whales can move with pace through the water. In the North Pacific, some humpback whales migrate from Alaska to Hawaii (4,800 kilometres) in as few as 32 days.

Population

Before the 1985 ban on commercial whaling, humpback whale populations were severely reduced (perhaps by as much as 90 to 95 per cent). In 1970, its population was so threatened that the U.S. listed all humpback whales in its territory as endangered.

Thankfully, its numbers have improved since 1985 and it’s now listed as having ‘Least concern’ status according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Commercial whaling is no longer a major threat but humpbacks are still hunted in some places, such as the St Vincent and Grenadine islands in the Caribbean and Greenland which both use the Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling Quota permitted through the International Whaling Commission (IWC). Greenland, for instance, has a quota allowing for up to nine humpbacks to be killed each year.

A recent IWC assessment of Southern hemisphere humpbacks estimated that overall numbers were at around 70 per cent of the number of whales thought to live in that region before hunting began.

It’s estimated that there are currently between 120,000 and 135,000 humpback whales in waters around the world.

What do they eat?

Like many other large whales, the prey of humpback whales are tiny creatures. They feed on plankton, shrimp-like crustaceans (krill) and small fish. They sieve a huge amount of water through their baleen plates, which act as filters to separate food from liquid.

Humpbacks have been observed using special techniques to help them herd and disorient their prey. Bubble net feeding is one of those techniques – the whales blow big waves of air bubbles to condense their prey. Once they have them where they want them, the humpbacks lunge upward through the circular bubble net and open up wide to take in their food.

Humpback whales consume up to 1,360 kilograms (1.36 tonnes) of food every day though they tend to generally fast during migration and when spending time at their breeding grounds (when they dip into their fat reserves). However, researchers have tracked some individuals engaging in opportunistic feeding during migration and breeding periods.

Singing and breaching behaviours

Humpbacks are famous for their ability to sing – letting out complex cries and noises, often for hours on end. Male humpback whales are particularly vocal during the mating season, which is thought to be their attempt to attract a potential female partner.

These songs are studied by scientists to decipher their meaning.

A study published in September 2022 found that humpback songs easily spread from one population to another across the Pacific Ocean.

Ellen Garland, author of the study and a marine biologist at the University of St Andrews, said it can take just a couple of years for a song to move several thousand miles. The study showed that whales in Australia were passing their songs to others in French Polynesia, who, in turn, gave songs to whales in Ecuador.

One of the bestselling albums of all time captures some of these impressive songs – ‘Songs of the Humpback Whale’ was recorded in 1970 and released that same year by Dr Roger Payne, founder of Ocean Alliance. Listen to one of those songs here on YouTube.

Humpback whales are a favourite of whale watchers which shouldn’t come as a massive surprise – their high levels of activity mean they put on a great display for anyone watching!

They rise nose-first out of the water (spy hopping), slap the water with their pectoral fins and use their massive flukes to propel themselves through the water and sometimes completely out of it.

This behaviour is called breaching. Exactly why whales breach is still not clear to us. There are a few different possibilities – including courting other whales, shaking parasites off their skin or simply to make a sound by splashing back in the water (they may be communicating to other whales, including signalling a warning).

Baby whales that have lost their mothers have been observed breaching repeatedly – probably to send both a visual and audio signal to its mother.

The other strong possibility is that the whale is playing. There may not be any other reason apart from the explanation that jumping out of the water and splashing back down is fun!

Take a look at a phenomenal breach below (this clip, recorded in Australia, went viral and has been viewed 76 million times to date!):

Threats to humpback whales

Entanglement in fishing gear

Like other whales, humpbacks can become entangled in different types of fishing gear. This can cause injury, fatigue, compromised feeding and even death.

Estimates from 1995 showed that entanglement was responsible for a five per cent annual mortality rate among humpback whales and it’s likely to have increased in recent years (with greater population numbers and more opportunities for fishing gear to come into contact with humpbacks).

A study in 2019 found that 25 per cent of humpback whales surveyed had entanglement scars. UK charity Whale Wise is currently investigating this matter with its Scars from Above project.

Vessel strikes

Accidental vessel strikes can injure or kill humpback whales. Humpback whales are vulnerable to vessel strikes throughout their range, but the risk is much higher in coastal areas with heavier ship traffic.

Environmental change and pollution

Climate change and pollution can lead to loss of habitat as waters become warmer.

Humpback whales forage for food in higher latitudes (northern hemisphere) and lower latitudes (southern hemisphere). Climate change is causing our polar regions to lose sea ice, year on year, and this has a knock on effect on prey distribution for whales. This leads to changes in feeding behaviour, creates nutritional stress and reduced reproduction for humpbacks.

Plastics and micro plastics in the ocean pose a threat to whales, along with all other marine mammals and fish. Chemical pollutants entering into the water ecosystem are also a serious threat to all creatures in our ocean.

Humpback whales, like other whales, uses noise to communicate so increased noise pollution from vessels interferes with this ability.

Natural predators

The only natural predator of the humpback whale is the orca. Orcas have been observed attacking and eating humpbacks (always calves).

Humpback whales have been witnessed coming to the aid of grey whales under attack from orcas. Check out the video below filmed for BBC’s Planet Earth.

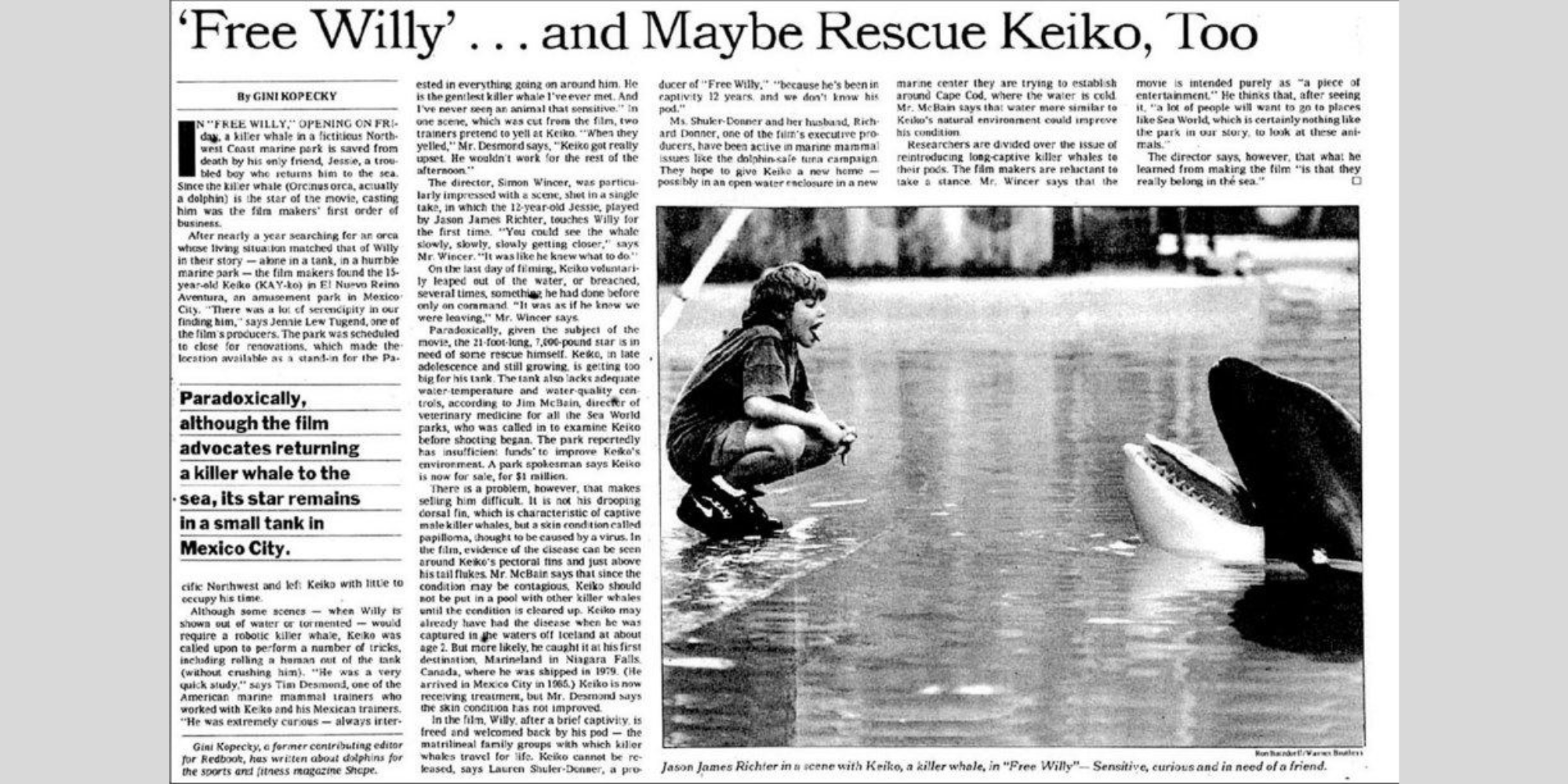

Whales That Made a Mark on the World: Keiko

Main Picture: Mark Berman

In our third blog on whales who’ve captured the attention of the world and the hearts of people, we take a closer look at the male orca Keiko.

Due to his appearance in the popular 1993 film Free Willy, a huge groundswell of affection was generated for Keiko along with interest from people all over the world in his welfare and his future.

Early life, capture and captivity

Keiko (previously known as Siggi or Kago) was born in 1976. He was captured when approximately two years old, near Reyðarfjörður in Iceland, and sold to an aquarium in Hafnarfjörður (which also housed other orcas over the years, including Tilikum).

In 1982, Keiko was sold to Marineland in Ontario, Canada, where he was set to work performing for the public. There are reports that he developed skin lesions, which indicated poor health, and was also bullied by older orcas.

Three years later, he was sold to Reino Aventura theme park in Mexico City. It’s there that he was given the name ‘Keiko’, which means ‘lucky one’ in Japanese.

Sadly, he would go on to spend 11 years of confinement in a tank designed for bottlenose dolphins, not helped by the fact that he grew considerably in size during his time there. Keiko couldn’t dive at all and when he was idly floating, his tail almost touched the bottom. While he had dolphins for company, there were no other orca at the amusement park.

Another challenge for Keiko was the hot weather. Accustomed to the cold waters of the North Atlantic during his early years, he now had the hot Mexican sun beating down incessantly on him.

Theme park staff filled the tank with tap water, which was chlorinated, and brought in salt to replicate the ocean water but it was all a foolhardy endeavour. The natural ocean environment could never be reproduced in an inland manmade tank.

Keiko had a collapsed dorsal fin due to lack of mobility, being kept in tanks for close to two decades.

Free Willy

After several years in Reino Aventura, Keiko was chosen to perform in the film Free Willy, which tells the story of a young boy who befriends and eventually manages to release a captive orca from a marine park. The 1993 film was a box office success, earning $153 million worldwide, from a budget of $20 million.

The film proved to be popular with children and adults alike, who connected with the inspiring story of the orca who made it back to the wild.

But that story was at odds with what Keiko faced after the film crew left Mexico City. He was still living in exactly the same conditions at the theme park and still captive, far from being the ‘Free Willy’ of the film title.

Keiko fans weren’t happy with his situation and started an international letter writing campaign, Free Keiko, to have him returned to the wild, preferably to his family group in Iceland.

Earth Island Institute received more than 400,000 phone calls from people, predominantly children and their parents, calling to know what they could do for Keiko and what they could do for whales.

Warner Bros, who had made the film, were also spurred into action to help the orca. Several organisations came together to meet with the owners of Reina Aventura to see what could be done to help Keiko.

One possibility was to move him to another aquarium but nobody wanted to take him due to the skin disease he had developed (as it could have spread to other orcas in captivity). When the idea to return him to his native habitat began to get legs, Warner Bros approached the Earth Island Institute to serve as the orca’s custodian.

Reino Aventura – which had reportedly paid $350,000 for Keiko – donated him to the newly founded Free Willy-Keiko Foundation which the Earth Island Institute had set up.

Rehabilitation and Release

The first step in the plan was to move him to a better facility while his health improved and in January 1996, he was airlifted to Oregon Coast Aquarium and homed in a new state-of-the-art tank. Some $7 million had been raised by the public to help fund the new facility.

Keiko spent just over two years there while everything was put in place for his move back to Iceland where he’d been captured 19 years previously. It was a massive operation, given that this had never happened before – a captive orca being transported by plane back to its native habitat.

The journey was mapped out from the West Coast of the U.S. across the Atlantic Ocean to Iceland. He weighed approximately four tonnes at the time and was transported on a U.S. Air Force C-17 Globemaster III aircraft, safely contained in a specially made transfer tank onboard.

In September 1998, with international media and millions of people following the story, Keiko arrived at Klettsvik Bay in the Vestmannaeyjar islands region.

He was initially housed in a sea pen where he was given training designed to prepare him for his eventual release. This included how to hunt for food (though there was critical commentary that humans don’t understand complex orca feeding habits so aren’t best placed to teach them to a whale).

Keiko also undertook supervised swims in the open ocean. Thorbjorg Valdis Kristjansdottir spent two years working with Keiko during his rehabilitation and remembers him as “as unbelievable animal. He absolutely had a definite personality. I spent a lot of time alone with him, and I talked and talked and talked to him. He would just kind of dance in the water.”

In the summer of 2002, he was in good shape and in the best position to be freed into the open ocean. He was spotted departing Icelandic waters in early August, following some orcas. Unfortunately though, he didn’t integrate with the pod.

His journey was tracked via a radio signal tag attached to his dorsal fin. A month later, Keiko was found in Norway’s Skalvik Fjord where he was interacting with humans.

The team looking after his welfare moved to Norway and continued to monitor him via boat-follows for the next 15 months. Although he occasionally approached groups of wild orcas, he remained at a distance from them (approximately 100-300 metres).

While Keiko had successfully fed himself during his swim from Iceland to Norway, he later needed to be fed by the team looking after him.

Keiko was the first (and to date only) captive orca to be fully released back into the ocean but, sadly, he did not live a long life. He died on 12 December 2003 in Taknes Bay in Norway, after becoming lethargic and despite being given antibiotic treatment.

Pneumonia was determined as the probable cause of his premature death – he was just 27 when his life ended.

Keiko’s Impact

It was not the happy Hollywood ending that everyone had wished for. In the aftermath of Keiko’s death, some media outlets called his rehabilitation and release a “complete failure” because he didn’t integrate with a pod of orca and because he still had dependencies on humans (seeking them out for interactions and for food).

It’s been pointed out though that the failure to reunite with his family unit may have been down to circumstances – they may no longer have been alive or he may have been merely passing through that part of Iceland when he was taken as a young whale. It could have been wrong place, wrong time for a family reunion to have occurred.

In the big scheme of things, his rescue should be seen as a success. Keiko wouldn’t have lived much longer in the theme park in Mexico, with his physical and mental health continuing to deteriorate (one expert said he may only have lived for a few more months there).

Not only did he get removed from that facility but he made it through a period of readjustment in Oregon, then moved to the sea pen in Iceland and then finally lived out his days in the ocean, back where he came from.

Keiko’s rescue has served as a model for other cetacean rescues and as an inspiration that if enough people lobby and come together, a life beyond captivity can become a reality for whales.

In 2013, a New York Times video, Freeing Willy, took a retrospective look at his return to the ocean. Take a look below:

Check out previous blogs in this series

The WeWhale Pod Episode 3 - Mariano Sironi

Our guest for this episode of The WeWhale Pod is Dr Mariano Sironi, Scientific Director of the Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas, a non-profit organisation headquartered in Argentina with the purpose of protecting whales and their environment through research and education.

Amongst the topics, Mariano talks about the Southern Right Whale research programme that's been in the Peninsula Valdes since 1971, what drew him to working with whales and some of his memorable interactions with whales over the years.

You can find out more about Mariano and his colleagues' work on the Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas website. Thanks to Skalaa Music for post-production.

Take a listen to the episode below:

And you can listen to previous episodes on our Podcast Page.

Deep dive…into Narwhals

The narwhal (Monodon monoceros) is a medium sized toothed whale that’s only found in Arctic waters. As it lives in remote places, in a habitat that’s dark for half the year and covered in ice, the narwhal is not easy to access in order to study. This means there’s still a lot we have to learn about this cetacean.

Narwhals are best known for the unusual tusk that comes out of their heads, giving them the name ‘unicorns of the sea’ and lending them an often mythical status (Inuits in Greenland call them by a name which means “the one that points to the sky”).

They’ve adapted to become one of the deepest diving marine mammals, capable of diving to depths of more than 1,800 metres and spending lengthy periods of time below 800 metres, a feat not many marine creatures can sustain.

Born as blue-grey, narwhals change colour during their lives – to black-blue as juveniles and then to a mottled grey colour as adults. And finally to a white colour as they reach old age.

They have a robust (some would call it sausage-shaped!) body with a small bulbous head and little to no beak. They have short flippers and don’t have a dorsal fin (they do have a ridge on their back though). Even though they are toothed whales, people say narwhals sometimes look more like dolphins or porpoises, save for the tusk on their head and their bigger size.

The narwhal’s colouration contributed to its name, which comes from the old Norse language. The prefix ‘nar’ means ‘corpse’ and ‘hval’ means whale. The name ‘corpse whale’ refers to how its skin colour resembles that of a drowned sailor.

Length-wise, a narwhal generally measures anywhere between 4 and 5.5 metres and it weighs in at 1.5 to 1.9 tonnes. The species has a single blow hole, which is typical of toothed whales. We know that narwhals live to at least 25 years of age and can live up to 50.

What’s commonly referred to as the tusk on its head is actually an enlarged tooth with millions of nerve endings inside it. This tusk is most commonly found on males (only three per cent of females grow one and they’re not as prominent as the males’ tusks). Some whales actually have two tusks.

The tusk is spiralled to the left and can grow up to three metres long. It had been thought that the tusk helps males with their dominance but new drone footage from 2017 in Canada revealed narwhals stunning fish with their tusks before eating them.

Take a look at the clip below:

Where do narwhals live?

Narwhals are year-round inhabitants of the Arctic Ocean and are spotted in Canada, Greenland, Alaska, Norway and Russia.

The majority of the world’s population spend the winter under the sea ice in the Baffin Bay – Davis Strait area (which is between Canada and western Greenland). This area is also a habitat for bowhead whales, belugas, fish and seabirds.

While they live all year in the Arctic Circle, they do move around – to ensure they don’t get trapped by pack ice at the height of winter, and to spend time in coastal waters and fjords in the summer.

Narwhals travel in groups, usually between 15 to 20 individuals although larger gatherings of hundreds have been observed.

When they travel together, the whales swim fast and close to the surface. Sometimes they float together motionless at the top of the ocean or they leap out of the water and then dive underneath in unison.

Population

The species is difficult to study, meaning population figures are very firmly estimates. It’s thought that there around 80,000 narwhals though other reports estimate there are 120,000.

The species was last assessed in 2017 for the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and was deemed to have ‘Least concern’ conservation status.

However, there are concerns about their population levels in specific regions (see ‘Threats to narwhals’ section below).

What do they eat?

Narwhals dive down deep to get their food, often to the bottom of the ocean. They’ve been known to dive to as deep as 1,800 metres and stay down there for 30 minutes. They feed intensely during the winter period and eat very little during the summer season.

Their primary prey includes halibut, shrimp, cod, squid and crab (when they find them on the seabed). They’ve an unusual way of eating – first finding their food through echolocation and then creating a kind of vacuum with their mouth to suck them up. As mentioned, researchers have observed narwhals using their tusks to stun their prey before eating them.

Threats to narwhals

Climate change/pollution

As their life cycle and habitat is so closely connected to life in the Arctic Circle, narwhals are thought to be the whale species most affected globally by climate change and the melting of the polar caps.

Interestingly, a study in October 2022 shows that narwhals are adapting to the climate crisis by delaying migration. It’s positive that they’ve developed an ability to adapt to the changing Arctic environment but unfortunately this change in their behaviour also involves an increased risk of becoming trapped under ice and drowning.

A 2021 study of narwhal tusks showed that in the past 20 years, the amount of mercury found in them has increased significantly, without a simultaneous shift in the species’ diet.

The researchers from McGill University in Canada attributed this rise to on-going fossil fuel combustion in South-East Asia and said it could also be due to changing sea ice conditions as the climate warms and changes the environmental mercury cycle in the Arctic.

Oil and gas development in this region also poses a threat to the species, with more opportunities for collisions and for increased noise pollution disturbing the narwhal’s normal behaviour.

Natural predators

The narwhal has few natural predators, due to its large size and its habitat in a remote location. One of its predators is the orca.

Less often, polar bears and walruses have been observed killing narwhals that have become trapped in shallow pools of water near ice, unable to move away.

Hunting

Inuit people have hunted narwhal for centuries for their flesh, blubber and tusks.

In 2004, Greenland’s government introduced, for the first time, quotas for hunting narwhal and banned the exportation of their tusks. Despite this, the population in east Greenland is still of major concern to the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources (a government advisory body that monitors the environment.

It has warned that narwhals are at high risk of extinction in this region and in 2021, it advised a ban on hunting in three key areas. You can read more in this news article in The Guardian which also explores the tensions between hunters and scientists in the East Greenland region.

The WeWhale Pod Episode 2 - Áine-lisa Shannon

Our guest for this episode of The WeWhale Pod is marine biologist and science communicator Áine-lisa Shannon.

Amongst the topics, Áine-lisa talks about how she connected with the ocean growing up in the West of Ireland and how there has definitely been a lot more public awareness of ocean sustainability and cetaceans in the last few years. And why you'll always find her by the sea, whether that's scuba diving, kayaking, surfing (which she says she isn't great at but enjoys!) or just reading a book.

You can find out more about Áine-lisa's work on her Instagram page. Thanks to Skalaa Music for post-production.

Take a listen to the episode below:

And you can listen to previous episodes on our Podcast Page.

Passionate about whale protection? Five documentaries you need to see…

Want to educate yourself about whales and the issues they face around the world? Documentaries are a great way to stay informed – we’ve put together five of our top recommendations.

The Whale and the Raven

Director Mirjam Leuze’s film is centred around the remote Gill Island, just off the northwest coast of British Columbia, Canada. It’s a biodiverse area at the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest. Along with the whales and ravens namechecked in the title, the island is also home to wolves.

Two whale researchers, Hermann Meuter and Janie Wray, are drawn to the island to establish the Cetacea Lab. It studies this unique marine environment where humpback whales, orca, fin whales and porpoises live.

But a Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) exporting plant is being planned in the nearby community of Kitimat, bringing different factions into conflict. The whale researchers, the Gitga’at First Nation, the gas industry and the British Columbia Government are all players in what will unfold and the impacts on whales and other wildlife that call this region home.

2019. 1 hr 41 mins.

Born to be Free

A ground breaking documentary made by three women, all of whom are free-divers who love to swim with dolphins and whales (Gayane Petrosyn, Tatian Beley and Julia Petrik). It investigates the dark and murky world of trading wild sea mammals.

The idea for the film was sparked by news headlines in 2013 about the export of 18 beluga whales from Russia to the U.S. The sale was eventually blocked (in no small part due to campaigners around the world). While the three free-divers were delighted to hear the news, they were also left wondering what was the fate of the belugas.

The team set out to find them, a journey that brought them to remote parts of Russia. It also made them witnesses to shocking treatments of whales, dolphins and walruses, fuelled by human greed.

2016. 1 hr 24 mins.

Blackfish

The highly influential and often shocking documentary came out in 2013, three years after the death of SeaWorld orca trainer Dawn Brancheau.

The unravelling of exactly what happened on the day of her death serves as the jumping point into the documentary. It then follows the story of Tilikum who spent only one year of his life as a wild orca in Iceland before he was captured and sold first to Sealand of the Pacific in Canada and then to SeaWorld Orlando.

It forensically traces the environment and actions that shaped Tilikum’s behaviour and the tragic outcomes that ensued (the death of Dawn Brancheau was the third human fatality he was involved with). The film also reflects on the sad and lonely life of Tilikum himself, who would go on to die four years after the documentary’s release.

Blackfish features plenty of other stories of whales in captivity and also highlights the death of trainer Alexis Martinez, fatally attacked by an orca at Loro Parque in Tenerife in 2009. One of Blackfish’s key strengths is the fascinating eye witness testimony provided by former SeaWorld orca trainers.

The film opened the eyes and minds of millions of people around the world about how orca are treated in captivity and the ethics of keeping them in marine parks in the first place.

2013. 1 hr 30 mins.

The Loneliest Whale: The Search for 52

This documentary is set around a goal – to follow an expert team of scientists searching for an elusive whale, the ‘52 Hertz Whale’.

It’s believed this whale (thought to be a fin or blue whale or possibly a hybrid of both) has spent its entire life in solitude and uses a frequency different from other whales. Both of these factors make it the loneliest whale in the world.

‘52’ was first discovered in 1992 when his mating call was picked up by US Navy underwater surveillance in the Pacific Ocean, and the story went viral thanks to a 2004 New York Times article.

The film, directed by Joshua Zeman, follows the bioacoustics team’s quest to find ‘52’ and weaves in other stories to do with whales. These include the history of whaling, noise pollution and how it disturbs whales’ behaviour, and how the 1970 bestselling album Songs of the Humpback Whale introduced us to the beautiful vocals of our ocean giants and made us care more about their fate.

2021. 1 hr 36 mins.

Sonic Sea

Narrated by Rachel McAdams, this documentary takes a close look at sound in the ocean and how vital it is to the survival and prosperity of marine animals.

The increasing amount of human activity in our waters is distributing this delicate balance and the film goes through several examples of this. The impact of industrial and military ocean noise on whales and other marine life is explored, including the link to unexplained mass strandings and the more long-term disturbance to whales’ behaviour and their ability to thrive and survive.

Featuring interviews with a wide range of contributors including Ken Balcomb, the former pilot and acoustics expert who, more than 20 years ago, uncovered and exposed how naval sonar is killing whales.

2016. 1 hr.